Eighteen Colors of Mud Mansheng's Eighteen Styles of Purple Clay Teapots

Eighteen Colors of Mud Mansheng's Eighteen Styles of Purple Clay Teapots

Eighteen Colors of Mud Mansheng's Eighteen Styles of Purple Clay Teapots

Eighteen Colors of Mud Mansheng's Eighteen Styles of Purple Clay Teapots

Lu Na was born in Yixing in 1981 and graduated from Suzhou Dongwu Foreign Language School. She studied under Wu Peilin, a master of arts and crafts in Jiangsu Province, and systematically learned about Zisha clay techniques such as marbled clay and inlaid clay.

Mansheng Eighteen Styles Cultural Genes

Literati-led : Chen Mansheng (1768-1822), also known as Hongshou, Zigong, Mansheng, Manshou, Zhongyu Daoren, Mangong, Mangong, Jiagutingzhang, Xuxi Yuyin, etc., was a native of Hangzhou, Zhejiang. He once served as the magistrate of Liyang County.

One of the "Eight Masters of Xiling," he was proficient in all four calligraphic styles. He integrated poetry, calligraphy, painting, and seal carving into his teapot art, with each teapot bearing a unique inscription, achieving an artistic unity where "the teapot's value is enhanced by the inscription, and the inscription's fame is conveyed through the teapot." Leveraging his profound literary knowledge, he collaborated with Zisha masters to refine his teapot-making skills, pioneering the integration of inscriptions and line drawing art into the decoration of Zisha teapots, thus developing a completely new decorative concept and creating a series of elegant and outstanding works, such as the "Eighteen Styles of Mansheng." His works include *Zhongyu Xianguan Ji* and *Sanglianli Guan Ji*.

Philosophical carriers : The shapes of the teapots often draw inspiration from classical texts (such as the Analects and Zhuangzi), natural imagery (such as gourds and well curbs), and biomorphic objects (such as Han Dynasty tiles and column bases), conveying Confucian, Buddhist, and Taoist ideas. For example, the "a ladle of weak water" of the Shi Piao teapot symbolizes tranquility, while the "recurring cycle" of the Zhou Pan teapot symbolizes cyclicality.

The collaboration between Yang Pengnian and his sister: Mansheng designed the teapot, Yang Pengnian made the teapot, and Yang Fengnian decorated it, creating a division of labor model of "literati design + artisan production" to elevate the artistic level of Zisha teapots.

Innovation in inscriptions : Breaking through the limitations of traditional teapot inscriptions which only include the mark, Mansheng teapot inscriptions are mostly original poems and aphorisms. For example, the inscription "Ji Gu Si Yuan" on the Well Curb teapot is relevant to the teapot (well curb), the tea (drawing water), and the sentiment (remembering the source), and is known as the "three elements of teapot inscriptions".

Investigating things to acquire knowledge

The Mansheng Eighteen Styles are not only the pinnacle of Zisha (purple clay) teapot shapes, but also a concentrated embodiment of the Chinese literati's spirit of "investigating things to acquire knowledge"—transforming everyday teaware into a cultural carrier of philosophy, literature, and aesthetics. Its design philosophy of "the vessel carries the Dao" has had a profound influence on later generations of Zisha teapots and even Chinese craft aesthetics, and remains a typical case study in academic research on the interaction between literati and craftsmen.

For further analysis of the calligraphy of the inscriptions on a particular teapot, appreciation of authentic surviving pieces, or the market value of a Mansheng teapot, we can provide specific directions for in-depth discussion.

Mansheng's Eighteen Styles - Hemispherical Pot

The hemispherical teapot, one of the eighteen styles of Mansheng, is named for its hemispherical body, resembling a split hemisphere, symbolizing "the roundness of heaven and the squareness of earth, the harmony of yin and yang." The teapot features simple, full lines and a moderate capacity (approximately 300ml), suitable for brewing fermented teas such as oolong and pu-erh. It was a common teapot used by Qing Dynasty literati in tea ceremonies.

Inscription

"Plum blossoms and snow simmer on a lively fire; the mountain dweller is truly an immortal."

"Plum blossoms and snow-covered branches are simmered over a live fire"

Mei Xue : Adapted from Lu Meipo's poem "Snow Plum" from the Song Dynasty, which says "Plum blossoms must concede three parts whiteness to snow, but snow loses a touch of fragrance to plum blossoms," it is a metaphor for noble character.

"Living fire ": Su Shi's poem "Drawing water from the river to brew tea" states, "Living water must be boiled over a living fire," referring to the use of a living fire for brewing tea and emphasizing the refinement of tea ceremony. Brewing tea amidst plum blossoms and snow in the cold winter, with the tea smoke and plum fragrance blending together, is a way for literati to meet friends and transcend worldly concerns.

"The man in the mountains, is he an immortal?"

Translation of Chu Ci :

Adapted from Qu Yuan's "Nine Songs: The Mountain Spirit" ("山中人兮芳杜若"), "芳杜若" is changed to "仙乎仙".

"The man in the mountains is like an immortal, drinking the marrow of stone and forgetting the years," which strengthens the Taoist reclusive character.

Double meaning :

Surface layer: Praising the hermits in the mountains as immortals;

On a deeper level: It satirizes the worldly pursuit of fame and fortune, suggesting that one should find peace and tranquility in drinking tea.

The "world within a pot" of the hemispherical teapot is in line with the Taoist legend of "Master Hu" (Fei Changfang of the Eastern Han Dynasty who entered a pot to cultivate Taoism), transforming seclusion from a physical space into a spiritual realm. For example, the inscription "A man in the mountains, an immortal, an immortal" resolves the contradiction between "transcending the world" and "entering the world" in the tea ceremony.

During the Tang Dynasty, Lu Hongyi lived in seclusion on Mount Song and called himself "The Hermit of Mount Song". His poems, such as "Looking for the Immortal Steps" and the Mansheng teapot, both express his longing for "transcending the world". The "brewing tea over a live fire" on the hemispherical teapot realizes the cultivation of immortality as an elegant daily practice, reflecting the wisdom of the literati that "great seclusion is in the city".

From Qu Yuan's "The hermit in the mountains, fragrant as the fragrant Du Ruo" to the Mansheng teapot's "The hermit in the mountains, a celestial being indeed a celestial being," the image of "the hermit in the mountains" has undergone a thousand years of transformation, ultimately solidifying on the Zisha teapot as the ultimate carrier of the literati spirit. The hemispherical teapot, using tea ceremony as a medium, fuses Taoist cultivation of immortality, Confucian reclusion, and the unity of tea and Zen within a small space. Its inscription "A celestial being indeed a celestial being" is both a poetic response to Lu Hongyi's "love of immortals" and a contemporary interpretation of Tao Yuanming's "a heart far removed from worldly affairs, a place naturally secluded." When we caress this Zisha teapot, which embodies the spirit of "plum blossoms and snow-covered branches, brewed over a living fire," we touch not only the warmth of the clay but also the "sun and moon in the teapot" and the "poetry, wine, and pastoral life" that Chinese literati sought throughout history.

Stone Pot Lifting Beam

Chen Mansheng designed the Mansheng Well-Roof Stone Teapot and commissioned the purple clay potter Yang Pengnian to make it. The inscription reads: "Water is offered on the left, wine on the right, learn from the immortals and Buddhas, and entrust them with both hands."

Buddhist imagery : "Holding hands together" is an allusion to the Vimalakirti Sutra, which says, "With the sword of wisdom, destroy the thief of afflictions," implying the piety of bowing to the Buddha with hands clasped in prayer.

Taoism's pursuit of "learning immortality" echoes the Han Dynasty's "Jiao Shi Yi Lin" which states, "Jade Spring Wine is what immortals seek." The circular design of the handle symbolizes the spiritual realm of "the circulation of the heavens" in the cultivation of immortality.

Contradictions in the literature :

The "Illustrated Study of Yixing Teapots" only lists the Well Curb Teapot and the Stone Teapot as two separate styles, without any record of them being combined. It is necessary to consider whether they were experimental creations by Mansheng in his later years or imitations of antiques during the Republic of China period.

Isolated evidence from literature :

Apart from oral traditions passed down by collectors, there are no records of this teapot shape in Qing Dynasty documents, and the Nanjing Museum database also has no related collections.

This teapot shape was not originally among the eighteen styles of Mansheng. It may have been named by later collectors who combined the characteristics of the Well Curb Teapot (straight body, flat lid) and the Stone Teapot (trapezoidal body, handle), and it is a derivative of the "Mansheng" style.

The prototype of the "stone dipper" :

The diao (铫) is an ancient water-boiling vessel. According to the Shuowen Jiezi, "Diao is a warming vessel." In the Han Dynasty, they were mostly made of bronze or pottery, while stone diao appeared in the Song Dynasty (such as the black-glazed stone diao from Jian kiln in Fujian).

Additional features for "lifting beam" :

Mansheng combined the stone pot with the handle, which not only preserved the simplicity of ancient pottery but also enhanced its practicality. It is a typical example of a literati pot that "imitates the ancients but does not blindly follow them".

A Study of Yixing Teapots (Illustrated) :

The record states that "Mansheng copied the Han Dynasty stone kettle, removed the three legs, added a handle, and inscribed it with the words 'The kettle's design and the skill of its maker are my own creations, not those of the Zhou people,'" clearly demonstrating its innovativeness.

"Illustrated Catalogue of Teapots"

The Japanese Okugenbo described the Shidiao teapot with a handle as "resembling Han dynasty artifacts in shape but with a transcendent charm; the handle spans like a rainbow, and the body of the pot is like a rock."

Cultural Imagery

The original inscription on the stone kettle handle reads: "The design of the kettle, the craftsmanship of its handle, are my own creations, not those of the Zhou dynasty."

It is emphasized that although this teapot is an antique imitation, it is not a simple copy, reflecting Mansheng's "learning from the ancients and transforming them".

The phrase "not from the Zhou Dynasty" subtly satirizes the blind revival of ancient styles in the Yixing clay teapot industry at the time (there were no Yixing clay teapots in the Zhou Dynasty), advocating that literati teapots should "interpret the past through the lens of the present."

The phrase “搏之工” is a homophone for “博之功”, echoing the concept of creation in the Book of Changes that “the superior man, when making tools, values their imagery.”

With its trapezoidal body, short spout, ear-shaped handle, flat bottom, and footless design, this teapot features simple lines reminiscent of the "remnants of the stone teapot" and is a typical example of "incorporating literary elements into the vessel."

The Mansheng Well-Curved Stone Teapot (with Handle) is not merely a tea-drinking vessel, but also a spiritual universe constructed by literati: the well-curved body symbolizes "uprightness and moderation," the curved handle alludes to "harmony and understanding," and the inscription's imagery of immortals and Buddhas points to "transcendence of the mundane world." As tea is poured into the pot, the inscription "Water on the left, wine on the right" ripples with the water, allowing the viewer to touch not only the warmth of the purple clay, but also the eternal pursuit of "purity, elegance, and eternity" by Chinese literati over millennia. This pursuit, as the inscription states, is "learning from immortals and Buddhas, employing both hands"—cultivating a detached mind while engaging with the world, achieving spiritual transcendence within the confines of a small teapot.

Hengyun Pot

Inspiration <br />The design inspiration for the Hengyun (Horizontal Cloud) teapot comes from Chen Mansheng's experience of watching a rainbow while taking shelter from the rain. According to the "Illustrated Study of Yixing Sand Teapots," Mansheng encountered a rainstorm on his way back from visiting a friend. After the rain, he saw a rainbow stretching across the sky, one end hidden in the clouds and the other end disappearing into the stream. He then conceived the teapot shape with the idea of "a rainbow hanging horizontally, floating in the clouds," initially naming it "Yinhong" (Drinking Rainbow), and later settling on "Hengyun" (Horizontal Cloud). This natural image not only reflects the literati's appreciation of the great beauty of heaven and earth, but also implicitly contains the Taoist philosophy of "the gathering and dispersing of clouds."

The profound meaning of the inscription : The inscription on the body of the pot, "This cloud's richness, when consumed, will not cause emaciation, it is the essence of immortals and scholars," is key to understanding its cultural connotations.

Yunyu : The phrase comes from Pi Rixiu's "Ten Poems on Tea Utensils in Response to Lu Wang - Tea Bamboo Shoots" from the Tang Dynasty, which says "Several pieces of Yunyu boil, year after year Lu Yu is empty", referring to the rich and beautiful tea soup like clouds.

The phrase "the scholars among the immortals" alludes to Su Shi's line "the scholars among the immortals are thin and not plump," using tea as a metaphor for Taoism, implying that tea drinkers are like immortals who eat clouds and drink dew, possessing both the integrity of a scholar and the transcendence of Taoism.

Romantic allusion : Some scholars have pointed out that "clouds" in traditional culture imply the pleasure of men and women (such as "clouds and rain"). The plump shape of the pot resembles the female figure, and the inscription may express Mansheng's affection for a certain woman.

Aesthetics of Form

The body of the pot is based on a flat and round shape, with a round and full belly that symbolizes the flow of clouds; the three nipple-shaped feet stand upright, which is both stable and gives it a sense of dynamism.

Lid : The lid is designed to fit the body of the pot perfectly. The knob is shaped like a nipple, and a silver ring is attached to the side through a perforation. It is exquisite and delicate.

Spout and handle : The straight spout extends naturally, and the ear-shaped handle has smooth lines, forming a contrast between strength and softness with the body of the pot, embodying the aesthetic concept of "harmony between nature and human craftsmanship".

Milk-shaped pot (milk-shaped pot, milk spring)

Milk Spring and Philosophical Reflections on Life

Inspiration <br />The design of the Ru'ou teapot is inspired by Lu Yu's description of "Ruquan" (乳泉, milk spring) in his "The Classic of Tea"—"The best spring water is that which flows freely from a stone pool filled with milk spring water." During his tenure in Liyang, Chen Mansheng observed a mountain stream gushing forth milk spring water and conceived the teapot's shape with the idea of "milk nourishing life," initially naming it "Ruquan" (乳泉, milk spring) and later "Ru'ou" (乳瓯, milk bowl). This imagery not only reflects the literati's capture of the spirit of nature but also subtly embodies the Taoist philosophy of "the highest good is like water."

The profound meaning of the inscription : The inscription on the teapot, "Milk spring and snow, refreshing my cheeks," is key to understanding its cultural connotations.

Milk Spring Snowflakes : Adapted from the Tang Dynasty poem by Pi Rixiu, "Several wisps of clouds boil, year after year Lu Yu is empty," describing the tea soup as rich and delicious as milk spring snowflakes.

"Qin wo yin jia" is an allusion to Su Shi's line "Fine tea is like a beautiful woman," implying that drinking tea can inspire a literati's poetic spirit, just as milk nourishes the body and mind.

Medical metaphor : The Qing Dynasty book "Yinshan Zhengyao" records that "milk spring can be used as medicine to prolong life," and the inscription may reflect Mansheng's pursuit of health preservation.

Pumpkin-shaped teapot

Literati Aesthetics

Inscription system : The inscription on the body of the pot reads "A hearty and warming drink of asparagus, brewed by Su Shi himself," which combines the artistic conception of Su Shi's "Drawing water from the river to brew tea" with the medicinal effects of pumpkin, thus constructing a health philosophy of "medicine and food sharing the same origin."

The spirit of seclusion

Pumpkins, with their many seeds, symbolize fertility and good fortune, while their long vines represent longevity and prosperity. This infuses the life-worshiping spirit of agrarian civilization into Zisha (purple clay) pottery.

The Tiannan Pumpkin Teapot with Handle subtly embodies Su Shi's reclusive sentiment of "planting oranges all over the garden." Its biomimetic design transforms the pastoral imagery into an elegant utensil for the study. For example, the inscription "handmade" on the Mansheng Teapot pays homage to Su Shi's practice of self-cultivation.

Elevating the tea-making process to a spiritual dialogue embodies the concept of "harmony between man and nature".

Differences between Pumpkin-Shaped Handle and Mansheng's Eighteen Styles

The charm of the pumpkin-shaped teapot lies in its dual nature: a vivid portrayal of agrarian civilization and a vessel for the spirit of literati. From the refined scholarly pursuit of "carrying a gourd while reading a precious book" by Mansheng to the technological integration of contemporary artisans, this type of teapot has always sought a balance between tradition and modernity, nature and humanity. When tea is poured into the pumpkin-shaped handle, and when fingers trace the vine-like patterns on the handle, we touch not only the warm, smooth texture of the purple clay, but also the fusion and continuation of millennia-old agrarian civilization and the spirit of literati. This dialogue across time and space makes the pumpkin-shaped teapot a "living cultural carrier," awakening with each brew and reborn with each touch.

Half-moon tile pot

Chen Mansheng's Crescent Moon Teapot is a pinnacle of literati purple clay art. Based on Han Dynasty roof tiles, it blends the philosophical concept of "half" with the refined taste of literati, forming a unique aesthetic symbol.

Form and Origin

Poetic Transformation of Han Dynasty Roof Tiles

The body of the teapot is modeled after a semi-circular roof tile from the Han Dynasty, as seen in the collection of the Shanghai Museum. The two characters "延年" (Yan Nian) are inscribed on the body, directly taken from auspicious phrases on Han roof tiles (such as "长生未央" (Chang Sheng Wei Yang) and "与天无极" (Yu Tian Wu Ji). Roof tiles, as components of ancient architecture, have both practical and aesthetic functions. Mansheng transformed them into a Zisha teapot, endowing the object with a cosmological view of "harmony between man and nature".

Visual metaphor: The body of the pot is crescent-shaped, with an arc at the top and a flat bottom, subtly echoing the traditional Chinese cosmology of "round heaven and square earth". The short, curved spout and round handle form a symmetry, and the bridge-shaped knob echoes the "dang" part of a roof tile. The overall lines are simple like Han Dynasty clerical script, full of the spirit of metal and stone.

Mansheng's Literary Reconstruction

During his tenure in Liyang, Mansheng observed the "flying eaves and hanging bells, with light and shadow intertwined" on the roof tiles of Qin and Han dynasty residences. He then used the shape of the roof tile and the imagery of a crescent moon to design the "Half-Moon Roof Tile Pot." His friend Guo Pingjia once wrote a poem: "The roof tile is half-open, the moon is not yet full, but its clear light shines into people's eyes," highlighting the beauty of the interplay between reality and illusion in the pot's shape.

Innovative Breakthrough : Traditional roof tiles are flat, but Mansheng has made them three-dimensional. The curvature of the pot body is precisely controlled at 180 degrees, maintaining the simplicity of the roof tile while ensuring its practicality. The visual center of gravity is stable.

The philosophical code of "half"

"Not seeking perfection is the key to longevity."

The inscription on the body of the pot uses the phrase "Great perfection seems incomplete" from Lao Tzu, with "half" symbolizing "whole," implicitly containing the wisdom of the Confucian "Doctrine of the Mean" and the Daoist "emptiness, stillness, and maintaining the center." For example, the inscription on the pot in the Shanghai Museum's collection encircles the belly of the pot, and the clerical script is simple and ancient. The last stroke of the character "全" is elongated like a water droplet on a roof tile, enhancing the dynamic feel of the text.16

The characters “延年” (Yan Nian) refer both to the inscription on a roof tile and to the health benefits of drinking tea. Lu Yu’s “The Classic of Tea” states that “tea is most suitable for people of refined conduct and frugal virtue.” Man Sheng used the inscription to elevate tea drinking to the practice of “self-cultivation.”

The pursuit of perfection through unity

Another classic inscription reads, "Unity brings completeness, and together with Master Hu, we prolong our lives" (from the Xiling Seal Society collection). It alludes to the story of "Master Hu" (a Han Dynasty immortal), implying that drinking tea is like cultivating immortality, requiring a state of "half-awake, half-drunk." In terms of the inscription's layout, "Unity" and "Completeness" are placed on either side of the teapot, creating a visual tension of "yin and yang complementing each other."

Spatial Narrative : The inscription does not cover the entire body of the pot, deliberately leaving blank spaces, such as the two blank spaces between "can prolong life" and "drink from the sweet spring", forming a literati composition of "sparse enough for a horse to gallop", which is in line with the artistic conception of "silence speaks louder than words"7.

The Wisdom of Life from "Half" to "Whole"

"The interplay of reality and illusion"

The body of the pot is hollow, and the handle is circular, forming a Taoist concept of "seeking reality within emptiness". Guo Lin, a friend of Mansheng, once wrote "Ode to Half-Earthen Pot": "Half but not lacking, full but not overflowing, the empty room gives birth to whiteness, and auspiciousness is still."

Aesthetics of Imperfection

Mansheng deliberately preserved the "imperfections" of the teapot body, such as the slightly concave shoulder and the crooked knob, subtly echoing the aesthetic pursuit of "remaining mountains and waters" by Bada Shanren, a painter from the late Ming and early Qing dynasties. This "beauty of imperfection" breaks away from the traditional neatness of Zisha teapots, endowing the objects with the personality and emotions of literati.

The sun and moon shine long in the pot

The crescent-shaped teapot is not merely a tea-drinking vessel, but also a spiritual universe constructed by literati: the "half" of the body symbolizes the imperfection of life, the "whole" in the inscription points to the pursuit of eternity, and the circular handle metaphorically represents the cyclical philosophy of "recurrence." When tea is poured into the pot, the inscription "not seeking perfection" ripples with the water, and the viewer touches not only the warmth of the purple clay, but also the eternal pursuit of "purity, elegance, and eternity" by Chinese literati over thousands of years. This pursuit, as the inscription states, is "to prolong life with the teapot"—achieving spiritual transcendence and eternity within the confines of this small teapot.

Flying Goose Longevity Pot

The inscription on the abdomen reads: "The wild goose gradually approaches the chime, enjoying food and drink; this is the vessel of Sang Zhu Weng, whose name will be remembered forever."

Note: 衎 (kàn) means peace and happiness; 桑諎翁 (Sangzhu Weng) is Lu Yu's pen name; 不刊 (bù kān) means indelible.

The image of a wild goose perching on a chime stone symbolizes the noble aspirations of tea connoisseurs and the solemnity of tea ceremonies, akin to the rites and music of ritual.

The phrase "Yinshi Kankan" originates from the Book of Songs (specifically the Lesser Odes), which subtly echoes Lu Yu's "The Classic of Tea," which states that "tea is most suitable for those who are refined in conduct and frugal in virtue."

Sang Zhuweng's tea utensils, which he claimed to inherit from Lu Yu's orthodox tea ceremony, were used to further his tea ceremony.

The inscription on this teapot, which will be remembered for generations, not only praises Lu Yu's virtues in tea but also hopes that it will become a lasting cultural symbol.

The Fei Hong Yan Nian teapot is a pinnacle of Qing Dynasty literati purple clay teapots. It was designed by Chen Mansheng (1768-1822), one of the "Eight Masters of Xiling," and made by the purple clay master Yang Pengnian (1772-1854). Its inscription, "The wild goose gradually approaches the chime, and the food and drink are delightful. This is the vessel of Sang Zhu Weng, and its name will be remembered forever," contains multiple cultural codes and demonstrates the spiritual core of literati purple clay teapots: "the vessel carries the way."

The inscriptions, through the metallic and stone-like quality of calligraphy and seal carving, incorporate personal creations into the "historical coordinate system," realizing the idea that "the pot becomes valuable because of the inscription, and the inscription is passed down because of the pot."

2. Textual exegesis of “磬” and “磐”

The character "磬" in "鸿渐于磬" may be a miscarving of "磐". The original text of the "Gradual Progress" hexagram in the Book of Changes is "鸿渐于磐". Mansheng may have changed "磐石" to "石磬" due to a mistake in the engraving or intentionally, using the imagery of a musical instrument to enhance the elegance of the tea set.

The Feihong Yannian Pot takes the shape of a Han Dynasty roof tile, the Book of Changes as its soul, the Tea Sage as its guide, and inscriptions as its structure.

When we gaze at the Zisha teapot inscribed with "Eternal Fame," we see not only a masterpiece of clay and carving, but also a spiritual landmark left by Chinese literati in the long river of history: they knew that the physical body is perishable, but believed that thought and art can be "immortal." The Flying Goose Longevity Teapot is the ultimate carrier of this "principle of immortality."

Tin-inlaid pot

The Dianhe Teapot is a pinnacle of Qing Dynasty literati purple clay art. It was designed by Chen Mansheng (1768-1822), one of the "Eight Masters of Xiling", and made by Yang Pengnian (1772-1854), a master of purple clay. Its shape and inscriptions carry profound cultural codes and demonstrate the spiritual core of literati purple clay "vessels carrying the Dao".

Symbolic translation of 钿合

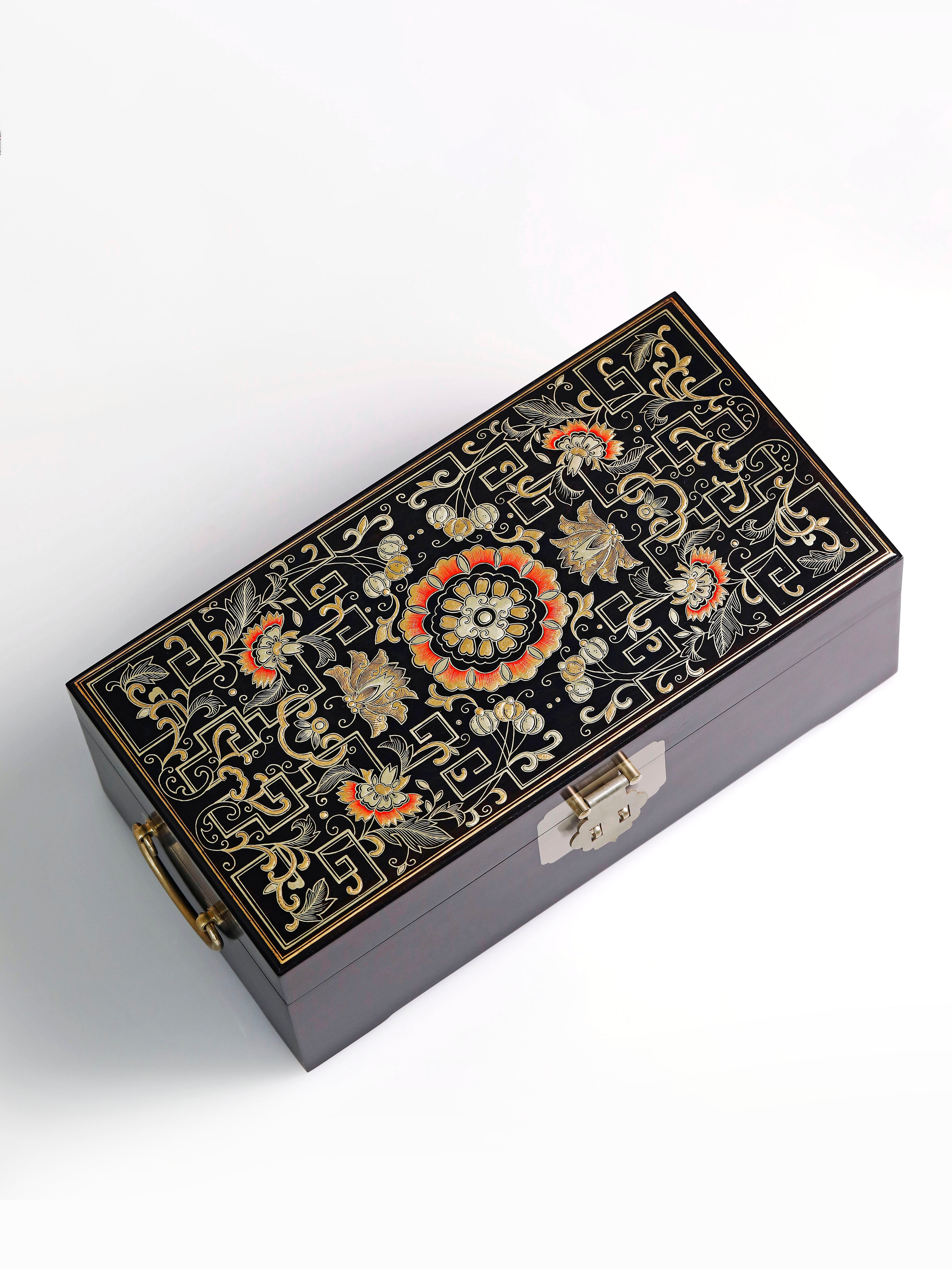

The Dianhe teapot is modeled after the Tang Dynasty "Dianhe" (钿盒), a dressing box inlaid with gold foil and mother-of-pearl, symbolizing love and beauty. Mansheng transformed the flat Dianhe into a three-dimensional piece, with the teapot body formed by two flat, round bodies interlocking. A wide, raised line adorns the center, both concealing the seam and subtly echoing the closed imagery of the "Dianhe." The Mansheng Dianhe teapot in the Palace Museum collection is 6.5 cm high and 5.2 cm in diameter. Its body is made of blended clay, with pearl-like inclusions resembling mother-of-pearl, becoming increasingly lustrous and jade-like after being steeped in tea.

The Dianhe teapot's shape exudes a graceful charm: its straight spout is elegant and upright, its ear-shaped handle is light and agile, its flat-set lid fits perfectly with the body, and its flat knob resembles a miniature version of the teapot. This design breaks away from the traditional masculine style of Yixing teapots, echoing the assessment by Guo Pingjia, a friend of Mansheng, in his book "Tao Ya" that "Mansheng teapots are not merely drinking vessels, but carriers of the literati's spirit." The Mansheng Dianhe teapot in the Shanghai Museum is made of golden Duan clay, a sweet, tender, and dense material that turns golden yellow after firing. The body is engraved with "Dianhe Dingning, Gaizhu Chajing" (钿合丁宁,改注茶经), the inscription carved with a "single-stroke side-edge" technique, the lines varying in thickness to simulate the erosion effect of Han Dynasty bricks.

Inscription meaning

The emotional metaphor of "Dianhe Dingning"

Origin : The inscription "钿合丁宁" (Dianhe Dingning) is adapted from Bai Juyi's "Song of Everlasting Regret" from the Tang Dynasty, specifically the line "Only old objects can express deep affection; a dianhe gold hairpin is sent as a token of love." This originally referred to the vow of love between Yang Guifei and Emperor Xuanzong of Tang, using a dianhe box as a token. Mansheng applied this to teaware, imbuing the Yixing teapot with emotional value, as stated in "A Study of Yixing Teapots": "Mansheng teapots are objects for literati to express their feelings."

Cultural Reconstruction of "Revised Annotations on the Classic of Tea"

The symbolic value of Lu Yu: The "Revised Annotation of the Classic of Tea" echoes the classic status of Lu Yu's "Classic of Tea." Mansheng, through the inscription, associates the dianhe teapot with the Sage of Tea, reinforcing its cultural orthodoxy. The inscription on the bottom of the Feihong Yannian teapot in the collection of the Palace Museum, which features a raised wild goose and the seal script for "Yannian," forms a double metaphor of "text-image," which is similar in effect to the inscription on this teapot.

The mystery of "Hushan's" identity

Some dianhe teapots bear the inscription "Hushan," but the identity of this person remains unclear. Some scholars speculate that "Hushan" might have been a close associate or commissioner of Mansheng, as the *Qianchen Mengyinglu* records that Mansheng often collaborated with literati such as "Jiang Tingxiang" and "Guo Pinjia," but the exact correspondence still needs verification. This mystery adds to the mystique of dianhe teapots, making them among the most "literati-intimate" works of Mansheng's teapots.

The authenticity of "making teapots for his wife" <br />It was rare for Qing Dynasty literati to make teapots specifically for their wives; more often, they made them for concubines or mistresses. It is necessary to verify whether Chen Mansheng's family letters mention "Zhou" and the matter of making teapots.

Textual Exegesis of “钿合” and “钿盒”

"钿合" and "钿盒" are actually the same thing, with "合" being interchangeable with "盒". Mansheng's choice of the character "合" may be because the body of the pot is made of two parts that fit together, subtly echoing the philosophy of "yin and yang harmony" in the Book of Changes. This kind of wordplay is common in Mansheng's pot inscriptions, such as the "Hehuan Pot" which is shaped like a "hecha" (a type of cymbal), and the inscription "Eight cakes as the head, for the phoenix and the luan, those who obtain the female prosper" also contains the meaning of "harmony".

The "reminder" of objects and the "eternity" of the spirit.

The Dianhe Pot takes the shape of a Tang Dynasty dianhe box, the "Song of Everlasting Regret" as its soul, the Tea Sage as its guide, and inscriptions as its bones, constructing a literati world where "the vessel carries emotions".

patchwork pot

From monk's robes to tea utensils

The term "百衲" (bǎi nǐ) originates from the "百衲衣" (bǎi nǐ yī) of Buddhist monks (made of patchwork fabric), symbolizing the Zen Buddhist idea of "cherishing things and cultivating the mind."

Translation of the teapot shape : During the Qing Dynasty, Zisha artists pieced together different clay materials or patterns to create a teapot body that mimicked the effect of patched clothing, hence the name "Hundred Patch Teapot".

First recorded in the "Illustrated Study of Yangxian Sand Teapots - Supplement" in the late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China, it is described as "the clay color is mixed like a cassock, and the shape is simple and unadorned";

This pot shape is not recorded in the "Mansheng Pot Inscription", but some of the inscriptions (such as "Accepting the past and embracing the present") were used by later generations to decorate patchwork pots.

Zen aesthetics : the dialectic of fragmentation and wholeness ("Though patched in a hundred ways, the Dharma body remains indestructible"), the patchwork on the teapot symbolizes the egalitarian view that "all sentient beings possess Buddha-nature".

The Taoist metaphor is an embodiment of "great skill appears clumsy" from Zhuangzi, deliberately preserving the seams of the clay slabs in pursuit of "the ultimate beauty in imperfection".

Origin mystery :

Whether the patchwork teapot was inspired by the Song Dynasty patchwork zither (cracked lacquerware) and patchwork stele (rubbings collage), or directly transplanted the imagery of monk's robes, needs to be compared with fragments of Ming Dynasty purple clay teapots.

The patchwork teapot was designed by Chen Mansheng (1768-1822), a scholar of the Qing Dynasty, and made by Yang Pengnian, a famous Zisha (purple clay) craftsman. It is one of the most thought-provoking representative works among the "Eighteen Styles of Mansheng". However, most of the existing "Qing Dynasty" patchwork teapots do not have reliable dates, and carbon-14 dating shows that some teapots labeled as being from the mid-Qing Dynasty contain 20th-century additives in their clay.

The eternal vitality of the patchwork pot

The charm of the patchwork teapot lies in its dual nature as both a material carrier and a spiritual totem. From Mansheng's "Do not underestimate the short robe" to contemporary reconstructions using marbled clay, from Buddhist asceticism to literati reclusion, this type of vessel has always sought a balance between tradition and modernity, practicality and aesthetics. When tea is poured into the patchwork teapot, when fingers trace the texture of the patches, we touch not only the warmth of the purple clay, but also the continuation and rebirth of a thousand-year-old cultural gene. This dialogue across time and space makes the patchwork teapot a "living cultural carrier," awakening with each brew and passing on its heritage with every touch.

Well curb

Original text : The spring water is fragrant, a paradise for immortals, its joy is endless.

Historical allusions

"Water of the Immortals" :

Adapting from the passage in "Liezi: Tang Wen" that "there is a sweet spring on Penglai Immortal Mountain, which can grant immortality if one drinks from it," the tea soup is elevated to "immortal elixir."

"Joy Never Ends" :

Originating from the poem "Ting Liao" in the Minor Odes of the Book of Songs, it means "endless enjoyment" or "unending pleasure". The inscription "Chang Le Wei Yang" is commonly found on bronze mirrors from the Han Dynasty.

-The Pleasures of Tea: Su Shi's "Fine tea is like a beautiful woman."

-The Joy of Life: Zhang Dai's eccentric view that "one cannot befriend someone without a quirk, for they lack deep feelings."

The uniqueness of the inscription on the Mansheng teapot

This inscription is the only one of its kind recorded in the "Illustrated Study of Yixing Teapots" (the Well-Lan Teapot in the collection of Nanjing Museum). Unlike the usual admonitory style of inscriptions, it shows a more carefree Taoist spirit.

Well curb design :

The body of the pot is modeled after the well curb of Chengguan Temple in the Tang Dynasty (a famous scenic spot in Liyang), which concretizes the "water of the immortals" into a tangible scene of drawing water.

The spout is deliberately thickened at the base to imitate the axis of an ancient well pulley, reinforcing the "immortal" symbol.

Yang Pengnian (Designed by Chen Mansheng) Antique Well Curb Teapot

The Yang Pengnian (designed by Chen Mansheng) Antique Well Curb Teapot is a pinnacle of Qing Dynasty literati purple clay art. Its shape and inscription carry cultural codes spanning a thousand years, showcasing the core literati spirit of "the vessel carries the Dao." Based on the ancient well curb of Lingling Temple in Liyang during the Tang Dynasty, this teapot was designed by Chen Mansheng (1768-1822), one of the "Eight Masters of Xiling," and crafted by the purple clay master Yang Pengnian (1772-1854). It is a prime example of the combination of "epigraphic research and tea ware aesthetics" among Mansheng teapots.

Ancient well from the Tang Dynasty

The inspiration for this antique-style well curb teapot comes from the Tang Dynasty stone well curb of Lingling Temple in Liyang County (now housed in Liyang Phoenix Park). Carved in the sixth year of the Yuanhe era of the Tang Dynasty (811 AD), this well curb was created by the eminent monk Cheng Guan, and the inscription records a historical scene of Buddhist offerings. When Mansheng served as the magistrate of Liyang County, he accidentally discovered this ancient artifact and transformed its flat inscription into a three-dimensional form, adapting it into the design language of a Zisha teapot. The teapot's body is cylindrical, mimicking the outline of a stone well curb; the bridge-shaped knob simulates the well curb's handle; and the bottom is inscribed with "Amantuo Shi" (Sanskrit for "the gathering place of the gods"), forming a dual metaphor of "text-image."

Metallic Qi

Inscriptions : The inscriptions on both sides of the pot are as follows:

Side A : "In the sixth year of the Yuanhe era of the Tang Dynasty, on the fifteenth day of the fifth month of the year Xinmao, the monk Cheng Guan built a permanent stone well railing and stone basin for Lingling Temple, to be used for perpetual offerings. The master craftsman was Chu Qing Guo Tong."

Side B : "This is a stone from Nanshan, which will be used to make a well curb. May it be passed down for thousands of generations, and may its name be linked to Buddhism. May it be used to cultivate merit and virtue, and may it never decay. May those who share in this great blessing surpass even Maitreya. Mansheng wrote this inscription on the Tang Dynasty well at Lingling Temple for Ji'ou's enjoyment."

The antique-style well-shaped teapot is modeled after an ancient well from the Tang Dynasty, imbued with Buddhist inscriptions, and guided by the refined tastes of literati.

Mansheng Jizhi Pot

[Origin of pot shape]

The name "Ji Zhi" originates from Ji An (courtesy name Changru), a famous minister of the Han Dynasty . The Records of the Grand Historian describes him as "arrogant by nature, straightforward, and intolerant of others' faults," known for his outspokenness and courage to remonstrate. Chen Mansheng incorporated the character "Zhi" (直, meaning upright) into the teapot, using the vessel to convey his philosophy and remind scholars to uphold integrity.

Inscription Interpretation

"Bitter yet delicious, upright in nature, Prime Minister Gongsun finds it as sweet as wine."

"Bitter but delicious":

Tea has a bitter taste but a sweet aftertaste, which is a metaphor for a virtuous person who is poor but keeps himself pure and his virtue will be remembered. It is an adaptation of the Book of Songs: "Who says that tea is bitter? Its sweetness is like that of water chestnuts."

The teapot has a wide belly and deep capacity, making it suitable for brewing strong tea, which has the characteristic of producing saliva after bitterness.

“Straighten its body” :

The body of the teapot is as straight as bamboo, the three-bend spout is strong and without curves, and the handle is as tall as the spine of an admonishing minister, echoing the "Straight, square and great, even without practice, there is no disadvantage" in the Book of Changes.

"Prime Minister Gongsun's food is as sweet as wine" :

Gongsun Hong (Prime Minister of Emperor Wu of Han) was good at flattery, forming a contrast between loyalty and treachery with Ji An, like "sweet wine and tea," which comes from Zhuangzi's saying, "The friendship between gentlemen is as bland as water, while the friendship between petty men is as sweet as wine."

The ironic meaning lies in contrasting the "sweet wine" of powerful officials with the "bitter tea" of upright officials, highlighting the values of scholars who would rather endure hardship than pursue vanity.

This teapot uses tea as a metaphor for politics and the vessel to record history, making it a perfect crystallization of Zisha art and the spirit of the literati. Its sharp inscription and austere shape are unique among the eighteen styles of Mansheng, and it remains a classic symbol of the literati's character to this day.

"Suffering yet fulfilling, upright in character" became the motto for scholars to cultivate themselves, which testifies to the artistic charm of the Mansheng teapot, which is "small in size but vast in its essence".

Stone Ladle Teapot

Inscription: To be firm without being fat is to live a long life.

The Story of the Stone Ladle: When Chen Mansheng was not serving as an official, he often traveled incognito through the streets, occasionally collecting antiques. One day, he saw a beggar begging on a street corner, with a stone vessel in front of him. Mansheng observed the vessel for a long time but couldn't find it. He then picked it up and examined it closely. He saw that the vessel had a unique shape, resembling a gourd but not quite. Although it appeared old, its elegant and simple appearance was undeniable. Looking at its base, he saw the inscription "Custom-made gourd by the Shao family of the Yuan Dynasty." Overjoyed, Mansheng immediately took out two taels of silver and bought it.

Yang Pengnian (Designed by Chen Mansheng) · Ladle Teapot

This original gourd-shaped teapot, 7.5cm high, was collected by Tang Yun, a calligrapher and painter from Shanghai. The body of the teapot is inscribed in running script: “Not fat but strong, thus longevity. Inscription by Man Gong on this gourd-shaped teapot.” The meaning is roughly: “A person should not be fat, but strong and healthy, thus they can live a long life.” The bottom of the teapot is stamped with the raised seal script “Amantuo Studio,” and below the handle is a small seal script “Peng Nian.” This teapot is also one of the “Mansheng Teapots,” designed and inscribed by Chen Mansheng, and made by Yang Pengnian.

Hehuan Pot

"Hehuan" means joy shared by two people. Anything that is divided in the middle, with the upper part facing up and the lower part facing down, and that is united as one, is called "Hehuan". The reader can understand its meaning by himself.

The shoulder is inscribed with "Trying Yangxian tea, boiling it with Hejiang water, the disciples of Su Shi were all delighted. Mansheng inscribed." The bottom of the pot is stamped with "Amantuo Studio," and the handle is stamped with "Pengnian." This pot is a masterpiece of collaboration between Chen Mansheng and Yang Pengnian.

Well-curb teapot

A clay pot?

A clay pot?

"Drinking tea purifies the mind, revealing the clear distinction between black and white," though not a direct quote from Mansheng, precisely captures the essence of the literati's tea-drinking spirit—tea is not merely a taste experience, but a mirror reflecting the inner self. If this were inscribed on a Yixing teapot, it would become a contemporary testament to the saying "a teapot is valued for its inscription": the moment the tea soup swirls in the pot, the interplay of black and white, is precisely a dialogue between nature and humanity, between matter and spirit. This dialogue began in Mansheng's "Amantuo Studio," continues on the desks of contemporary tea drinkers, and ultimately transforms into a refreshing sensation on the tongue and a clear mind with every cup raised.

Heavenly Chicken Pot

"When the celestial rooster crows, the precious dew overflows," subtly echoing the Taoist health philosophy of "the golden rooster announcing the dawn, and sweet dew descending to earth."

From Celadon Birds to Elegant Purple Clay Teapots

Origin Prototype : The earliest known celadon chicken-head pot can be traced back to the late Eastern Wu period of the Three Kingdoms (Note: The name "Celestial Chicken" originated in the Tang Dynasty and was initially called "Chicken-Head Pot"). Its shape is inspired by the mythical image of "Celestial Chicken" in the Classic of Mountains and Seas - "There is a large peach tree on Taodu Mountain, and there is a celestial chicken among its branches. When the sun rises and shines on this tree, the celestial chicken crows, and all the chickens in the world crow in response."1

Functional transformation : During the Western Jin Dynasty, the chicken head was a solid decoration, while during the Eastern Jin Dynasty, the chicken head evolved into a hollow spout, and the chicken tail became a curved handle, completing the transformation from a funerary object to a practical wine vessel. For example, the Eastern Jin Dynasty black-glazed chicken-head ewer in the collection of Nanjing Museum has a high crest and outstretched neck, and the curved handle is level with the mouth of the dish, reflecting the design philosophy of "harmony between man and nature".

North-South divide : During the Northern and Southern Dynasties, the Southern Tianji pot continued its elegant style, while the Northern pot featured dragon-head curved handles and beaded decorations, such as the white porcelain Tianji pot unearthed from the Feng family tombs in Jingxian County, Hebei Province. The pot has a fine body and a white glaze with a bluish tinge, marking the rise of porcelain-making technology in the North.

The Literati Reconstruction of the Zisha Heavenly Rooster Teapot

Xu Youquan of the Ming Dynasty created the Zisha Tianji (Heavenly Rooster) teapot, using pear-skin clay to imitate the texture of bronze ware. The spout, shaped like a rooster's head, is symmetrical with the animal-head ring, and the lid is decorated with a five-petaled plum blossom knob, transforming the solemnity of celadon into the simplicity and elegance of Zisha. Its inscription, "The Heavenly Rooster crows, the precious dew overflows," subtly echoes the Taoist health philosophy of "The golden rooster crows at dawn, and sweet dew descends to earth."

Mansheng Paradigm : Although Chen Mansheng did not directly design the Heavenly Rooster Teapot, his concept of "literati-made utensils" profoundly influenced later generations. For example, Pei Shimin imitated Chen Mingyuan's "Heavenly Rooster Teapot", with the body decorated with thunder and cicada patterns, the handle made into a dragon head spout, and the inscription "Drinking it brings good fortune, the heavenly rooster crows", which integrates the elements of bronze ritual vessels with the literati taste of Zisha pottery.

From figurative biomimicry to abstract freehand style

Glaze metaphors : The celadon glaze of the Yue kiln celadon rooster pot symbolizes "Eastern Jia and Yi wood", the jet black color of the Deqing kiln black glaze rooster pot implies "mysterious and profound", while the pure white color of the Xing kiln white porcelain rooster pot embodies the Confucian ideal of "a gentleman is like jade".

The Literati Deconstruction of the Zisha Heavenly Rooster Teapot

Material innovation : The Zisha Tianji teapot breaks through the glaze color limitations of celadon. For example, Pei Shimin's "Tianji Teapot" uses Duan clay and Zhu clay in combination. The spout is decorated with Zhu clay to dab the rooster's comb, and the texture of Duan clay on the body of the teapot imitates the corrosion of bronze, forming a visual effect of "metal and iron chiming".

From agricultural totems to the spirit of literati

Praying for good fortune in turbulent times : The frequent wars during the Wei, Jin, and Northern and Southern Dynasties reflected the popular folk worship of the celestial rooster pot, which is a homophone for "chicken" and "good fortune." For example, the Eastern Jin celadon celestial rooster pot unearthed in Pingba Machang, Guizhou, has the inscription "The owner's surname is Huang, given name Qi" on its belly, confirming its function as a funerary object for praying for blessings.

A reclusive sentiment : Pei Shimin created the "Celestial Rooster Teapot" during the War of Resistance Against Japan. The teapot is inscribed with "When the rooster crows, the world turns white," with the celestial rooster symbolizing national awakening. The handle is shaped like bamboo joints, alluding to the integrity of scholars who "have integrity even before they emerge from the ground."

Fighting

The teapot is modeled after the ancient measuring vessel "dou" and bears the inscription "Beidou is high, Nandou is low," which means "the harmony between heaven and man." The square-shaped body of the teapot symbolizes "distinguishing right from wrong and being upright and incorruptible."

The pot has a square-shaped body, four legs, and a straight spout. The inscription on the belly reads, "The Big Dipper is high, the Southern Dipper is low, drink this and live long, may you live a long and healthy life," combining astronomical imagery with auspicious blessings.

The term "Eighteen Styles" is not a precise number : historically, Mansheng participated in designing far more than 18 teapot styles. "Eighteen" is an approximation, meaning "auspicious" and "complete." This table focuses on the eighteen classic styles recorded in authoritative documents such as "Illustrated Study of Yixing Teapots."

Identifying the mark : Genuine Mansheng teapots often have the "Amantuo Studio" seal (Mansheng Studio name) on the bottom. The calligraphy of the inscription has a strong sense of antiquity. Later imitations often lose the form and spirit. For example, whether the lid line of the "Hehuan Teapot" is naturally "joined" is an important criterion for judgment.

Frequently asked questions

Use the FAQ section to answer your customers' most frequent questions.

Order

Yes, we ship all over the world. Shipping costs will apply, and will be added at checkout. We run discounts and promotions all year, so stay tuned for exclusive deals.

It depends on where you are. Orders processed here will take 5-7 business days to arrive. Overseas deliveries can take anywhere from 7-16 days. Delivery details will be provided in your confirmation email.

You can contact us through our contact page! We will be happy to assist you.