Taimu Mountain 2013 Silver Needle White Tea

Taimu Mountain 2013 Silver Needle White Tea

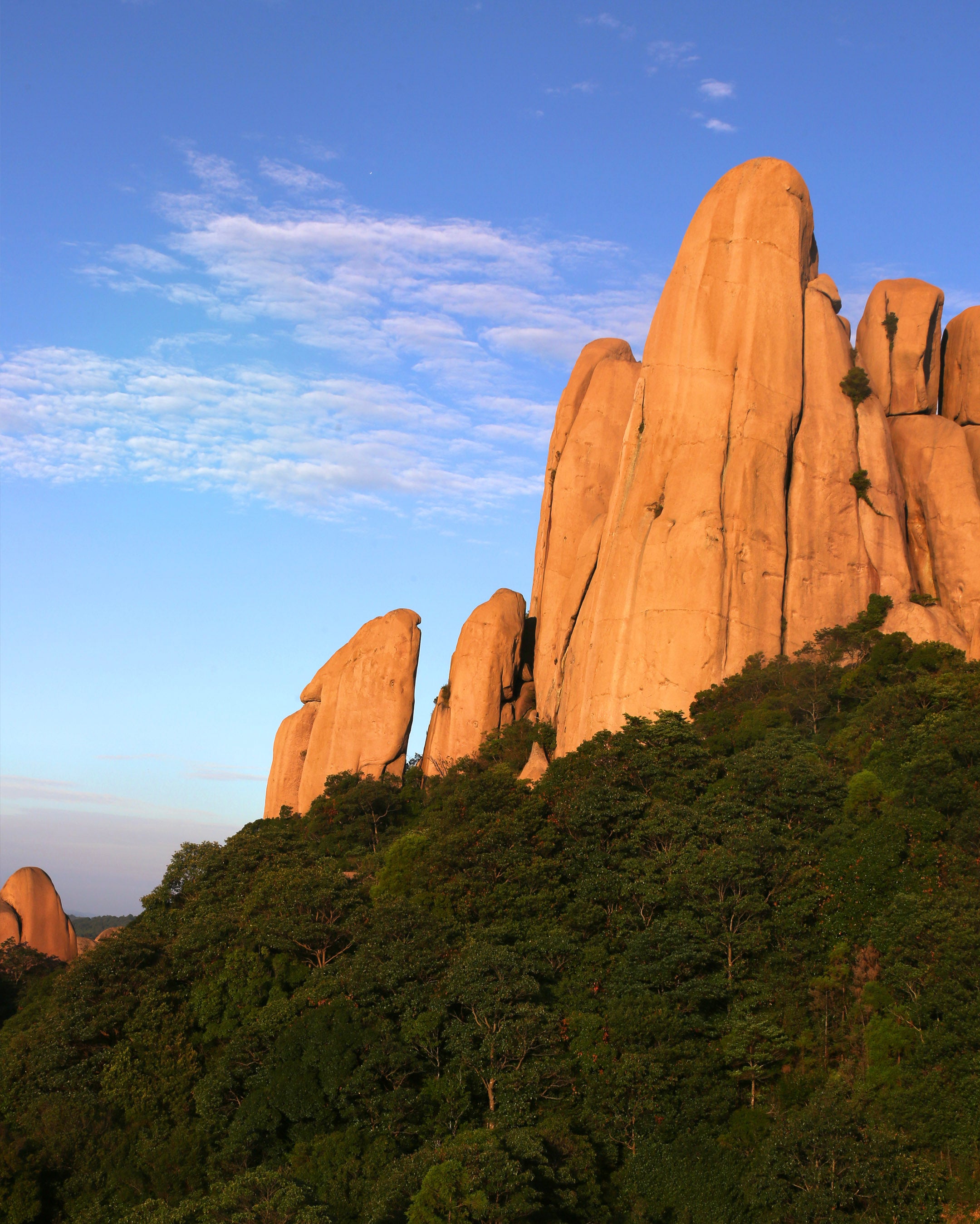

Visiting Tea Again in the Xinchou Year, I climbed the sacred Taimu Mountain in the early morning. Halfway up, sweat streamed down relentlessly. When I reached Bat Cave, the ascetic who once practiced quiet meditation here—lost in serene tranquility—was no longer there.

Beside Laoshi Temple, the white tea plants still grew in their most natural state. The Buddhist nun lived in harmony with the white tea and nature. Her story might drift through these mountains, but it would surely be etched deeply in my memory.

Thanks to the kind assistance of Abbot Tilian, I stayed at Xiangshan Temple.

In the evening, sudden lightning flashed and thunder roared, with a downpour pouring down.

The sweltering heat of the day was instantly washed away.

After the rain, a gentle breeze blew over Jiuli Lake beside the temple. We climbed upward along the heavenly steps and plank roads behind the monastery.

Ascending for about an hour, it felt as if we were ascending to heaven.

On our return journey, thick clouds and mist had long enshrouded the temple and mountain forests. Inside the courtyard, bells and drums rang in unison—their melody powerful, resounding yet deep and distant. We all stood breathless, daring not to speak loudly.

At four o’clock in the early morning of the next day, the sound of scripture chanting in the courtyard arrived as scheduled, rousing us from our sleep. It turned out that Buddhist monks were not as idle as the world imagined—they attended five classes every day, working harder than ordinary office workers.

Learning that both magnificent temples were founded by the great master Pinshan, I felt deep reverence.

Master Tilian followed the great master Pinshan at the age of 17. Recalling his teacher, the venerable master said:

Master Pinshan was born during the Republic of China. He founded Xiangshan Temple and built the Hall of Five Hundred Arhats.He endured countless hardships through more than ten years in prison. Only then did I understand—there is no boundary to Buddhism. Buddha resides both within the Buddhist community and in the mundane world, alongside you and me.

The white tea of Mount Taimu—unpan-fried and unrolled—relies on natural craftsmanship and absorbs the beauty of time. It carries orchid and grass aromas, embodying the ethereal essence of the sacred mountain and condensing the flavors of nature. Just like this tea-seeking journey: in landscapes, we behold integrity; through vicissitudes, we comprehend our original aspirations.

The senior Buddhist nun’s Wild Tea Garden

Celebrating the New Year in Bat Cave

Happy New Year🧨

The Turning of the Seasons

2013 Taimu Mountain Silver Needle White Tea

Tasting

The whole cake is tightly pressed and substantial. A light tap yields a dull sound, a mark of its 12 years of aging.

Insert a tea needle along the edge; a gentle push pries off intact pieces easily.

The concentrated dry fragrance exudes medicinal notes, honeyed charm, and mountain freshness — unique to aged Silver Needle.

Year : 2013

Grade : Superior Silver Needle

Origin : Taimushan Nature Reserve

Varieties: Wild sexually propagated varieties: Fuding Da Bai Cha, Da Hao Cha, mixed with native ancient tea trees from Taimu Mountain.

Process: Traditional process of natural withering and gentle drying without frying or kneading.

Appearance :

The cake is round and well-formed, with the color of the buds changing from white to silvery-gray, interspersed with old spots, and clear bud patterns. Traces of handwritten inscription "Gui Si Spring" are visible in the center. It feels firm to the touch and makes no sound when shaken, indicating the tight pressing.

Aroma :

The dry tea has a aroma of ripe grains, herbs, and honey sweetness, without any off-flavors. The aroma becomes more pronounced after breaking it open, with a delicate fragrance of downy hairs and a sweet jujube scent. Upon brewing, it initially has a light pine smoke aroma, which later transforms into a herbal and wild mountain fragrance. The honey aroma is dominant in the first 1-3 infusions, the herbal aroma gradually emerges in the 4-6 infusions, and the jujube aroma is persistent and lingering after the 7th infusion.

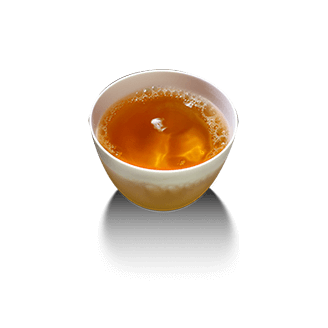

Tea liquor Color:

The rinsing infusion is pale apricot-yellow when the tea is moist, with white white fuzz floating on the surface and a delicate sheen on the cup. The first to third infusions are a light amber color with a slight golden ring; the fourth to eighth infusions turn into a deep amber color, maintaining its clarity; after the ninth infusion, it remains clear and smooth.

Tea liquor Color: 1-3 infusions are light amber, with white downy hairs floating on the surface and a slight golden ring ripples.

Tasting Notes :

The tea cake is dense — rinse twice before brewing.

1st–3rd infusions: Steep for 10–12 seconds. Sweet and slightly medicinal on the palate, with a cool, smooth tongue feel.

4th–8th infusions: Steep for 15–20 seconds. Honey-like syrupy liquor, with long-lasting lingering sweetness.

After the 9th infusion: Gradually extend steeping time. The final infusions remain sweet, offering excellent steeping endurance.

The texture is rooted in smoothness, with a sweet mellow taste sliding down the throat. It has a mild astringency and long-lasting lingering sweetness. After the 5th infusion, the lingering warmth in the throat and the gentle tea qi are bestowed by twelve years of aging.

Leaves After Infusion

The infused leaves are light brown, with buds and leaves fully unfolded and tough stems that don’t break easily — a clear sign of high-quality raw materials and proper aging. They feel flexible to the touch, with a lingering sweet fragrance and no stale odors.

Storage & Brewing Recommendations

For daily use, pry small pieces from the edge of the tea cake. Store the unused portion in an airtight, light-proof container. Wrap the remaining cake in rice paper and place it in a ceramic jar — it can continue aging for years, with the flavor becoming richer and more mellow.

This tea cake is tightly pressed and dense, locking in fragrance and condensing charm. As it ages, it becomes increasingly mellow, smooth and restrained — a true model of aged pressed tea.

The tea cake is tightly pressed and plump.

2013 Taimu Mountain Silver Needle White Tea

brewing

This tea has undergone 12 years of aging, with tight and compact bud clumps and a mellow, profound aged aroma. When brewing, it’s advisable to balance the characteristics of the tea cake and the quality of silver needle tea. We recommend using a gaiwan to release the aroma layer by layer, supplemented by boiling to fully unlock its residual charm.

1. Tea Preparation

The tea cake is dense and compact. Use a wide-blade tea knife to insert obliquely along the edges to find gaps, gently pry and separate layers. Take 5–6 grams of bud clumps with stems, keeping them intact. Avoid forced prying from the center of the cake to prevent tea breakage.

II. Brewing Method

Gaiwan Brewing (To Appreciate the Layered Aroma and Charm)

Utensils: 150ml white porcelain gaiwan

Water: purified water or spring water

Tea Amount: approximately 5 grams

Water temperature: 100℃ boiling water

Step:

After warming the gaiwan, add the tea leaves. Gently shake to smell the dry aroma — you can distinguish medicinal notes, honeyed undertones, and aged grain fragrance.

Pour water along the inner wall of the gaiwan to evenly moisten the tea leaves.

Serving time:

1st Infusion (Rinsing): 15 seconds

2nd–3rd infusion: 20–25 seconds, honey aroma prominent, smooth and sweet texture.

4th–6th infusion: 30–40 seconds, medicinal notes gradually intensify, and the liquor becomes rich and mellow.

After the 7th infusion: Steep the tea for over 45 seconds (extended steeping). The final infusions remain sweet, showcasing excellent steeping endurance.

Decoction Brewing (To Release the Aged Charm)

After the gaiwan brewing yields a faint flavor, take the used tea leaves and put them into a pot with cold water. Bring to a boil, then simmer on low heat for 2–3 minutes. The resulting liquor will have an amber color, a rich medicinal aroma, and a warm, smooth taste.

III. Tasting & Storage Tips

Storage: Wrap the tea cake in rice paper and store it in a purple clay jar or ceramic vat. Keep it in a cool, dry place — it can continue aging for 5–10 years, with the medicinal aroma becoming richer and more refined.

water quality

Choose qualified purified water; never use alkaline mineral water.

(For commercially available mineral water brands, their water sources and quality indicators vary. So-called "high-quality mineral water and mountain spring water" may cause loss of functional components and inhibition of aroma in tea.)

I:Effect of Alkaline Water on Green Tea

1. Effects on tea liquor color:

green tea:

Under alkaline conditions, chlorophyll is easily destroyed (chlorophyll stability decreases at pH > 8.0), causing the tea liquor color to easily change from bright green to yellow or dark yellow, resulting in turbidity, especially noticeable when brewed at high temperatures. Flavonoids (such as catechins) in green tea are easily oxidized in an alkaline environment, exacerbating the darkening of the tea liquor color.

black tea:

Theaflavins (bright orange-yellow) are easily oxidized to thearubigins (dark red) under alkaline conditions, and further generate dark brown, causing the soup color to change from bright red to dark and lose its transparency.

Other types of tea:

The color of oolong tea, white tea, and yellow tea may be darker due to alkaline water. The color of black tea (such as ripe Pu-erh) will become more turbid, and the color stability of aged aroma substances will also be affected.

2. Impact on taste and texture

Analysis reveals differences:

Tea polyphenols and caffeine: lead to insufficient concentration and bland taste. An alkaline environment inhibits the dissolution of tea polyphenols (bitter substances) and caffeine, reducing the bitterness of the tea soup.

Amino acids and sugars: Disruption of amino acid structure reduces the freshness and crispness.

Mineral influence: Alkaline hard water (containing more calcium and magnesium ions) combines with tea polyphenols to form insoluble precipitates (such as "cloudiness after cooling"), resulting in cloudy tea soup and a rough taste.

Balance of taste: It significantly affects the "richness" of tea soup for teas that rely on polyphenols to support their taste (such as raw Pu-erh tea and high-roasted rock tea), with no noticeable aftertaste and an overall taste that is bland and coarse.

3. Effects on aroma

Volatile aromatic substances: An alkaline environment may accelerate the degradation or transformation of aromatic substances (such as aldehydes and alcohols), resulting in a single aroma profile, especially in light-aroma teas (such as jasmine tea and Anji white tea), where the floral fragrance dissipates easily and may even develop a "mushy" taste.

Aged aroma and woody aroma: For fermented teas such as black tea and aged Pu'er, alkaline water may slightly highlight the aged aroma (pH>8.0) and suppress the fruity or honey aroma.

II:The adaptability of different types of tea to water quality

1. The interaction between the physicochemical properties of water and tea components

-

Hard water (>120 mg/L CaCO₃): Calcium ions combine with tea polyphenols to form precipitates, reducing the astringency of tea soup (EGCG binding rate can reach 23%), but losing antioxidant activity (Food Chemistry, 2018); Magnesium ions promote caffeine dissolution, and every 1 mg/L increase in magnesium can increase the caffeine concentration by 0.8% (Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2020).

-

Soft water (<60 mg/L CaCO₃): Theaflavin dissolution rate increased by 12%, and the brightness of the tea soup increased (L* value increased by 3.2), but the amino acid extraction efficiency decreased (Food Research International, 2019).

2. Supported by scientific experimental data

-

Longjing green tea brewing experiment (TDS = 50 vs 300mg/L): The amino acid content of the tea soup in the soft water group (1.2mg/mL) was significantly higher than that in the hard water group (0.8mg/mL), but the caffeine content was 18% lower (China Tea Processing, 2021); Sensory evaluation showed that the freshness score of the soft water group was 1.7 points higher (out of 9), while the body of the hard water group was 0.9 points higher.

-

Research on water quality suitability for Wuyi rock tea: Water containing trace amounts of sulfate (20-50 mg/L) can increase the dissolution of cinnamaldehyde, a characteristic aroma compound of cinnamon, by 24% (GC-MS detection), and significantly enhance the rocky aroma (Tea Science, 2020).

3. Water quality selection recommendations (based on tea)

|

Tea |

Ideal TDS |

Recommended pH |

Key ion requirements |

|

F.T.L. Green Tea |

30-80mg/L |

6.8 |

Ca²⁺<15mg/L, Mg²⁺<5mg/L |

|

F.T.L. Oolong Tea |

80-150mg/L |

7 |

HCO₃⁻ 40-60mg/L |

|

F.T.L. Black Tea |

100-200mg/L |

6.8 |

K⁺ 2-5mg/L, SiO₂ 10-15mg/L |

|

F.T.L. Pu'er Tea |

50-120mg/L |

6.8 |

Fe³⁺ < 0.1 mg/L |

4. Examples of the impact of special water quality

London tap water (high hardness): When brewing black tea, the formation of ochre-calcium complexes leads to "cold turbidity" appearing 30 minutes earlier, with the turbidity (NTU) of the tea reaching 12.5, which is significantly higher than that of the soft water group (NTU = 4.3) (Food Hydrocolloids, 2019).

Kagoshima hot spring water (containing sulfur): Sulfides react with theaflavins to form methyl flavonoids, which reduces the umami intensity of sencha by 37% (* Journal of the Japanese Institute of Food Science and Technology, 2022).

One Region, One Tea: Water quality from specific local water sources enhances the color, aroma, and taste of local tea, but using local water requires systematic professional knowledge and high costs. For non-professionals, mastering the basic principles of "softened purified water + temperature control" is far more practical than pursuing famous springs from the origin.

The precise matching of water and tea is essentially a dialogue of geographical genes, which needs to be built on a multidisciplinary system of geology, food chemistry, heat transfer and other disciplines, and cannot be covered in just a few lines of web pages.

The UK-based AquaSim laboratory has simulated 12 core indicators of Tiger Spring water. However, it lacks the original spring's microbial community (such as Nocardia tea-loving bacteria), resulting in a 27% difference in post-fermentation flavor. In addition, the operation is complex: it requires mastering the "listening to the spring while boiling water" method (stopping the fire immediately when the water first boils), and a temperature error of more than 3°C will disrupt the flavor balance.

The charm of tea ceremony lies in appreciating what suits one's taste.

A pot of purified water is enough.

Don't be trapped by the mystique of water quality.

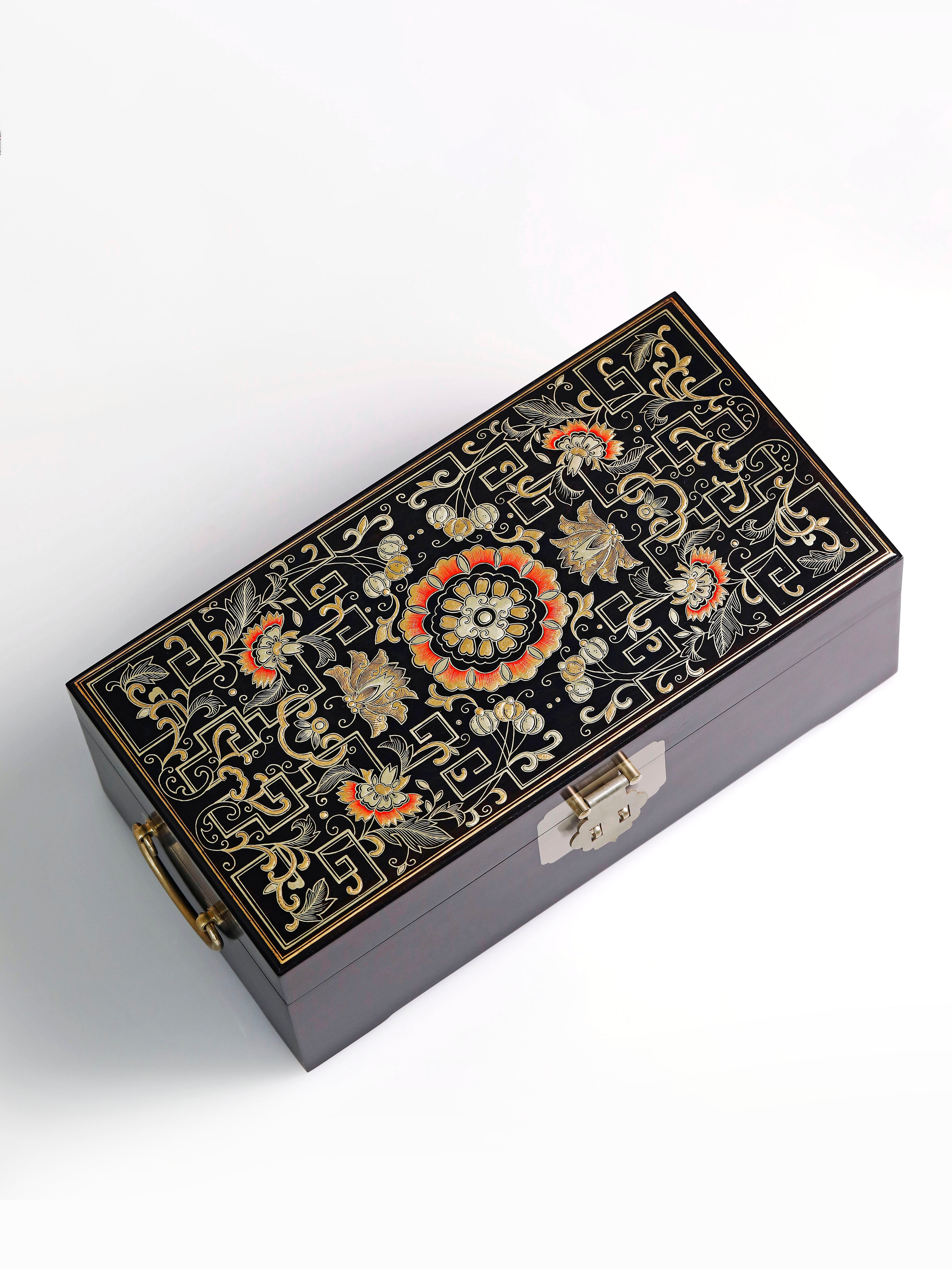

Wooden box packaging with a sealed bag inside.

White tea storage

White tea is cool in nature, growing cooler as it ages.

Three years of storage gives it medicinal value; seven years makes it a treasure.

White tea storage

White tea is cool in nature, growing cooler as it ages. Three years of storage gives it medicinal value; seven years makes it a treasure.

Avoid light, high temperatures, and odors.

Temperature & humidity: 15-25℃, 50%-65% (to prevent mold and loss of fragrance);

Light Protection & Ventilation: Keep away from direct sunlight (to prevent the decomposition of theaflavins and darkening of the tea liquor) and place in a well-ventilated area.

No odor interference: Keep away from sources of odor such as cooking fumes and spices.

Container selection

Short-term (within 1 year): Purple clay/ceramic jar with ventilation holes (for preservation);

Long-term (over 1 year): Aluminum foil bag (semi-vacuum) + moisture-proof cardboard box (aids conversion).

Taboo

Shelf life

The above storage method allows for long-term storage.