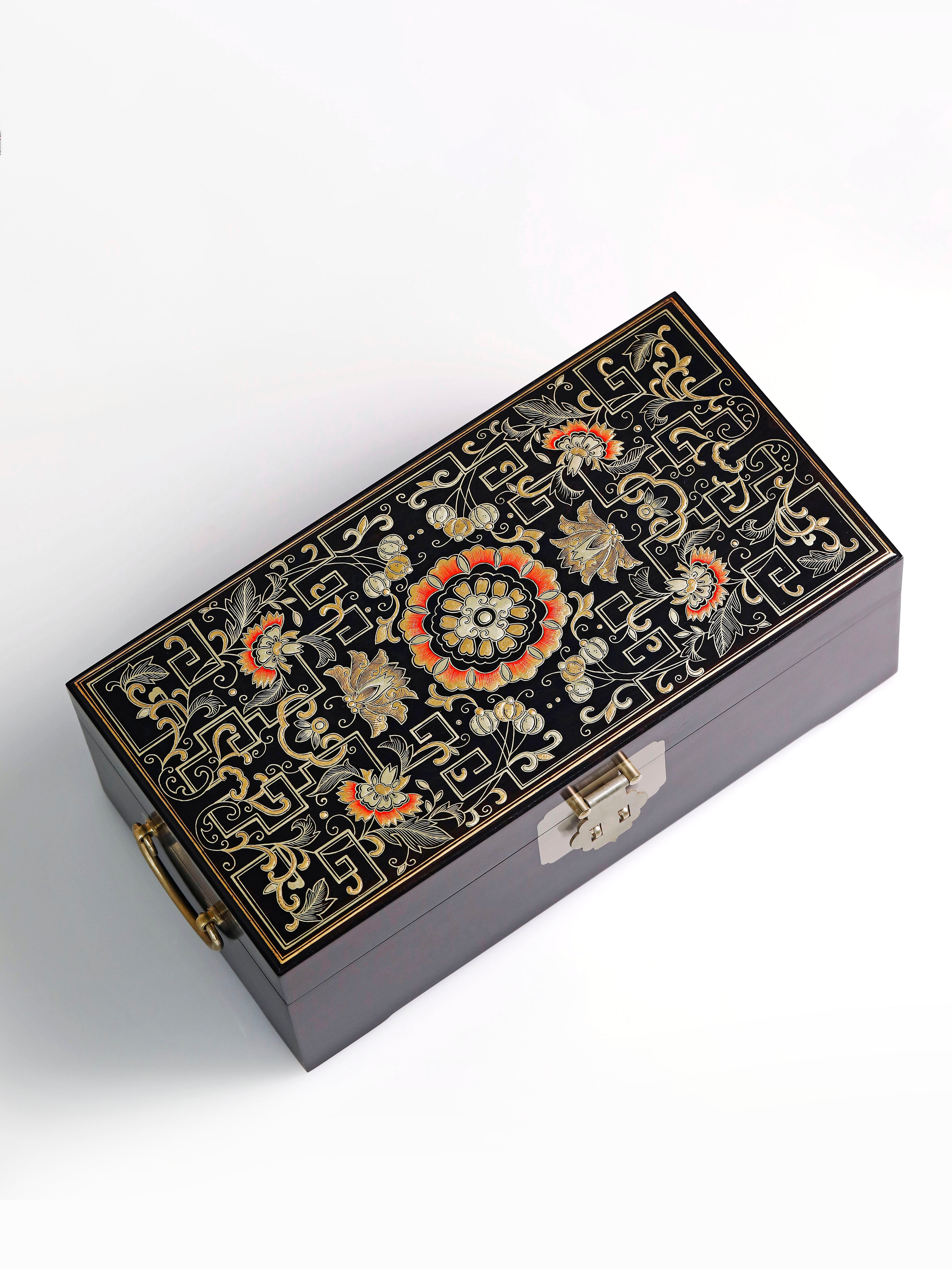

Yiwu Wild Mountain Old Tree Large Leaf White Tea

Yiwu Wild Mountain Old Tree Large Leaf White Tea

The morning mist over Yiwu Mahei hadn’t lifted when Li Aiguo slung his old bamboo basket over his shoulder and headed into the mountains. These mountain tea trees had been part of his life since childhood—he knew exactly which ancient trees bore the plumpest buds, which woods held the thickest mist, even with his eyes closed. The buds of the sun-facing "Hunchback Tree" in Mahei’s wilds carry a honeyed fragrance, while the leaves of the "Crack-in-the-Rock Tree" in the hollow are softer still.

Li Aiguo is from the Aini ethnic group, a branch of the Hani people. Back in the Ming Dynasty, his ancestors fled to this area to escape wars. Outside the ancient village, some old tea trees are 100 to 200 years old, and one is said to have been left behind by the Blang people who settled here even earlier. For the Wild Mountain Ancient Tree Large-Leaf White Tea, only the first batch of spring buds picked in the first few days after the Spring Equinox is used. "Picking less and leaving more" — this is not a mere formality, but the Aini people’s reverence for nature. Tea buds from artificially dwarfed trees or young saplings are not harvested for this grade of tea.

The picked buds and leaves are spread out on bamboo sieves. Making large-leaf white tea is simple in a way — it relies on the vitality of Yiwu's wild mountains and the wind of Mahei. Yet it’s also complex, as it requires "making tea according to the weather" — no picking on cloudy days, and avoiding sun exposure on sunny days. Though it uses natural withering followed by low-temperature drying over firewood to retain fragrance, the ever-changing weather holds the secrets of tea-making. Precisely because of this, the flavor of the tea varies every year and every day — that’s the will of nature.

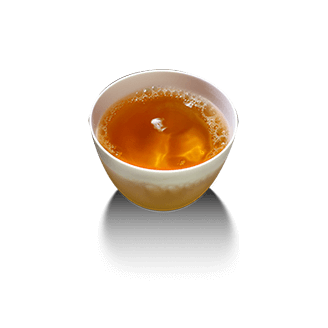

During the early spring tea season, his son returned from the Beijing tea market to help. In the evening, the father and son sat on the balcony drinking new tea: the tea soup was a pale golden and translucent, with a high aroma upon entry, but a refreshing, wild quality lingered after swallowing. "This year's tea is more fragrant than last year's!" the son exclaimed. Li Aiguo smiled and nodded: "There are only a few dozen old tea trees, and only this many spring buds. Last year, the weather was bad; we barely made two jin of this kind of tea before stopping. This year, during the 'tea festival,' perhaps because of our sincere hearts, there were many sunny days, and the strength of the wind was infused into the tea, hence the fragrance."

This Yiwu wild mountain old tree large-leaf white tea has dry tea leaves covered with silvery hairs, like being wrapped in a layer of light moonlight; it is sweet and mellow on the palate, yet it contains the strength of wild mountain ancient trees - it is a gift from nature, and also the taste of time brewed by the Li family guarding the mountains and trees.

一摘嫩蕊含白毛,再摘细芽抽绿发

——许廷勋《普茶吟》

First pluck the tender stamens cloaked in fine down;

Then pluck slender buds that burst forth in green.

— Xu Tingxun, "Ode to Pu'er Tea"

Only pluck the tips of spring buds; pick sparingly and leave more.

Only tea from wild mountain forests and century-old trees is harvested.

Yiwu Wild Mountain Old Tree Large Leaf White Tea

Appreciation

This white tea originates from old trees in the wild mountains of Mahei, Yiwu, and is made using the natural techniques of the Aini ethnic group. The key points for tasting it are summarized below:

Year: 2023

Gradel: Grade 1

Origin: Wild old trees in Mahei Mountain, Yiwu, Yunnan

Variety: species Mahei, Yiwu, Yunnan Sexually related Pu'er tea

Processing: Natural White Tea Craft of the Aini People

Dry tea appearance: natural texture of ancient tree buds and leaves

It appears as a single bud with one or two leaves, with plump, robust stems covered in silvery down like shattered moonlight, and a light brownish-green color without any impurities. A gentle sniff reveals a blend of wild mountain grasses and a subtle honey sweetness, exuding freshness and vitality.

Aroma: Layered and Progressive Aged Sweet Charm

Taste: Balanced Beauty of Clean Sweetness and Mellow Richness

It is smooth and sweet on the palate, with a refreshing and invigorating aftertaste that lingers in the throat for 15 seconds. The tea is at its best from the 3rd to the 6th infusion, with a thick and smooth texture and a "sweet yet potent" flavor. Even after the 10th infusion, the final brew remains sweet and refreshing, without any blandness.

Infused Leaves:

2023 tea liquor color

2020 tea liquor color

2015 tea liquor color

Due to its wild mountain old tree large-leaf variety, this white tea boasts rich internal substances and high steeping endurance. When brewing, it’s essential to balance "aroma release" and "preserving internal nutrients." The core simplified steps are as follows:

I. Utensil Selection

Utensils: Preferred choice is a 100-120ml white porcelain gaiwan (non-absorbent with good light transmission, allowing observation of the tea liquor’s golden fuzz). Secondary choice is an 80-100ml small-capacity purple clay teapot (impurities must be removed in advance).

Water temperature: Use 90-95℃ hot water (avoid boiling water to prevent damaging the active substances in buds and leaves, preserving the fresh mountain crispness). Preheat the utensils to stabilize temperature before brewing.

II. Tea Quantity & Brewing Time

Tea quantity: 5-6g (tea to water ratio 1:20), suitable for the characteristics of large-leaf varieties with thick leaves, avoiding being too strong and astringent, or too weak and tasteless.

Brewing Rhythm:

Rinse the tea: Quickly pour boiling water and discard immediately (to prevent aroma loss).

First 3 infusions: Brew for 15-20 seconds to highlight the floral and honey fragrance with clean sweetness.

Infusions 4-8: Extend each brew by 5-10 seconds to release the ancient woody fragrance.

After 9 infusions: Can steep for 30 seconds; the final brew still maintains sweetness and moisture.

III. Key Brewing Tips

Pour water slowly along the inner wall of the gaiwan (to reduce water flow impact and prevent bud/leaf breakage).

Leave 1/6 of the tea liquor at the bottom of the cup for the next brew to maintain stable concentration.

Avoid opening the lid frequently to reduce aroma evaporation and preserve the original flavor of its "natural craftsmanship".

Following these brewing methods can fully release the wild mountain charm of ancient trees, restoring the unique taste of soft sweetness on entry and fresh crispness after swallowing.

water quality

Choose qualified purified water; never use alkaline mineral water.

(For commercially available mineral water brands, their water sources and quality indicators vary. So-called "high-quality mineral water and mountain spring water" may cause loss of functional components and inhibition of aroma in tea.)

I:Effect of Alkaline Water on Green Tea

1. Effects on tea liquor color:

green tea:

Under alkaline conditions, chlorophyll is easily destroyed (chlorophyll stability decreases at pH > 8.0) , causing the tea liquor color to easily change from bright green to yellow or dark yellow, resulting in turbidity , especially noticeable when brewed at high temperatures. Flavonoids (such as catechins) in green tea are easily oxidized in an alkaline environment, exacerbating the darkening of the tea liquor color.

black tea:

Theaflavins (bright orange-yellow) are easily oxidized to thearubigins (dark red) under alkaline conditions, and further generate dark brown, causing the soup color to change from bright red to dark and lose its transparency .

Other types of tea:

The color of oolong tea, white tea, and yellow tea may be darker due to alkaline water. The color of black tea (such as ripe Pu-erh) will become more turbid, and the color stability of aged aroma substances will also be affected .

2. Impact on taste and texture

Analysis reveals differences:

Tea polyphenols and caffeine: lead to insufficient concentration and bland taste . An alkaline environment inhibits the dissolution of tea polyphenols (bitter substances) and caffeine, reducing the bitterness of the tea soup.

Amino acids and sugars: Disruption of amino acid structure reduces the freshness and crispness.

Mineral influence: Alkaline hard water (containing more calcium and magnesium ions) combines with tea polyphenols to form insoluble precipitates (such as "cloudiness after cooling"), resulting in cloudy tea soup and a rough taste .

Balance of taste: It significantly affects the "richness" of tea soup for teas that rely on polyphenols to support their taste (such as raw Pu-erh tea and high-roasted rock tea), with no noticeable aftertaste and an overall taste that is bland and coarse .

3. Effects on aroma

Volatile aromatic substances: An alkaline environment may accelerate the degradation or transformation of aromatic substances (such as aldehydes and alcohols), resulting in a single aroma profile, especially in light-aroma teas (such as jasmine tea and Anji white tea), where the floral fragrance dissipates easily and may even develop a "mushy" taste.

Aged aroma and woody aroma: For fermented teas such as black tea and aged Pu'er, alkaline water may slightly highlight the aged aroma (pH>8.0) and suppress the fruity or honey aroma.

II: The adaptability of different types of tea to water quality

1. The interaction between the physicochemical properties of water and tea components

- Hard water (>120 mg/L CaCO₃) : Calcium ions combine with tea polyphenols to form precipitates, reducing the astringency of tea soup (EGCG binding rate can reach 23%), but losing antioxidant activity (Food Chemistry, 2018); Magnesium ions promote caffeine dissolution, and every 1 mg/L increase in magnesium can increase the caffeine concentration by 0.8% (Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2020).

- Soft water (<60 mg/L CaCO₃) : Theaflavin dissolution rate increased by 12%, and the brightness of the tea soup increased (L* value increased by 3.2), but the amino acid extraction efficiency decreased (Food Research International, 2019).

2. Supported by scientific experimental data

- Longjing green tea brewing experiment (TDS = 50 vs 300mg/L) : The amino acid content of the tea soup in the soft water group (1.2mg/mL) was significantly higher than that in the hard water group (0.8mg/mL), but the caffeine content was 18% lower (China Tea Processing, 2021); Sensory evaluation showed that the freshness score of the soft water group was 1.7 points higher (out of 9), while the body of the hard water group was 0.9 points higher.

- Research on water quality suitability for Wuyi rock tea : Water containing trace amounts of sulfate (20-50 mg/L) can increase the dissolution of cinnamaldehyde, a characteristic aroma compound of cinnamon, by 24% (GC-MS detection), and significantly enhance the rocky aroma (Tea Science, 2020).

3. Water quality selection recommendations (based on tea)

| Tea | Ideal TDS | Recommended pH | Key ion requirements |

| F.T.L. Green Tea | 30-80mg/L | 6.8 | Ca²⁺<15mg/L, Mg²⁺<5mg/L |

| F.T.L. Oolong Tea | 80-150mg/L | 7 | HCO₃⁻ 40-60mg/L |

| F.T.L. Black Tea | 100-200mg/L | 6.8 | K⁺ 2-5mg/L, SiO₂ 10-15mg/L |

| F.T.L. Pu'er Tea | 50-120mg/L | 6.8 | Fe³⁺ < 0.1 mg/L |

4. Examples of the impact of special water quality

London tap water (high hardness) : When brewing black tea, the formation of oxalool-calcium complexes leads to "cold turbidity" appearing 30 minutes earlier, with the turbidity (NTU) of the tea reaching 12.5, which is significantly higher than that of the soft water group (NTU = 4.3) (Food Hydrocolloids, 2019).

Kagoshima hot spring water (containing sulfur) : Sulfides react with theaflavins to form methyl flavonoids, which reduces the umami intensity of sencha by 37% (*Journal of the Japanese Institute of Food Science and Technology, 2022).

One Region, One Tea: Water quality from specific local water sources enhances the color, aroma, and taste of local tea, but using local water requires systematic professional knowledge and high costs. For non-professionals, mastering the basic principles of "softened purified water + temperature control" is far more practical than pursuing famous springs from the origin.

The precise matching of water and tea is essentially a dialogue of geographical genes, which needs to be built on a multidisciplinary system of geology, food chemistry, heat transfer and other disciplines, and cannot be covered in just a few lines of web pages.

The UK-based AquaSim laboratory has simulated 12 core indicators of Tiger Spring water. However, it lacks the original spring's microbial community (such as Nocardia tea-loving bacteria), resulting in a 27% difference in post-fermentation flavor. In addition, the operation is complex: it requires mastering the "listening to the spring while boiling water" method (stopping the fire immediately when the water first boils), and a temperature error of more than 3°C will disrupt the flavor balance.

The charm of tea ceremony lies in appreciating what suits one's taste.

A pot of purified water is enough.

Don't be trapped by the mystique of water quality.

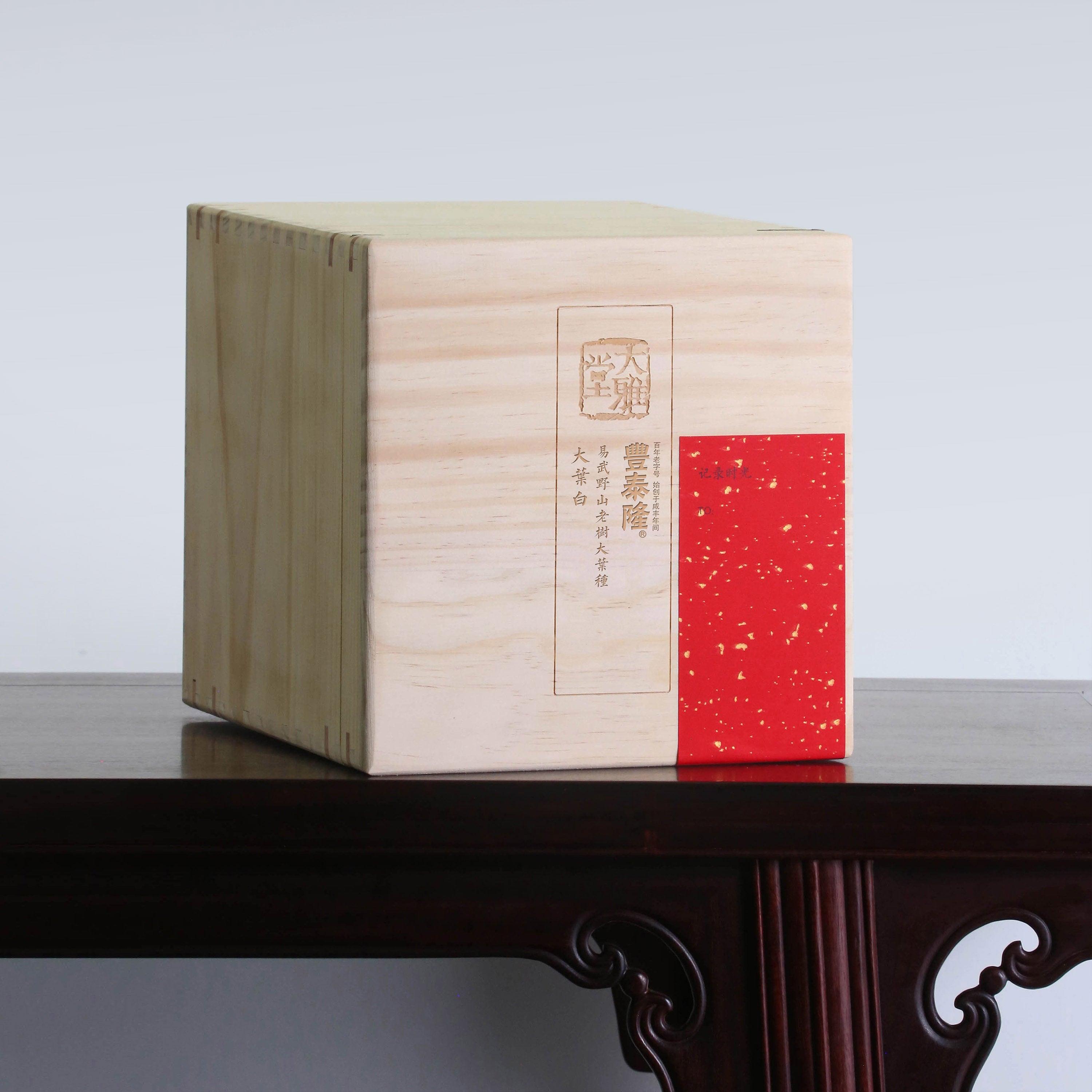

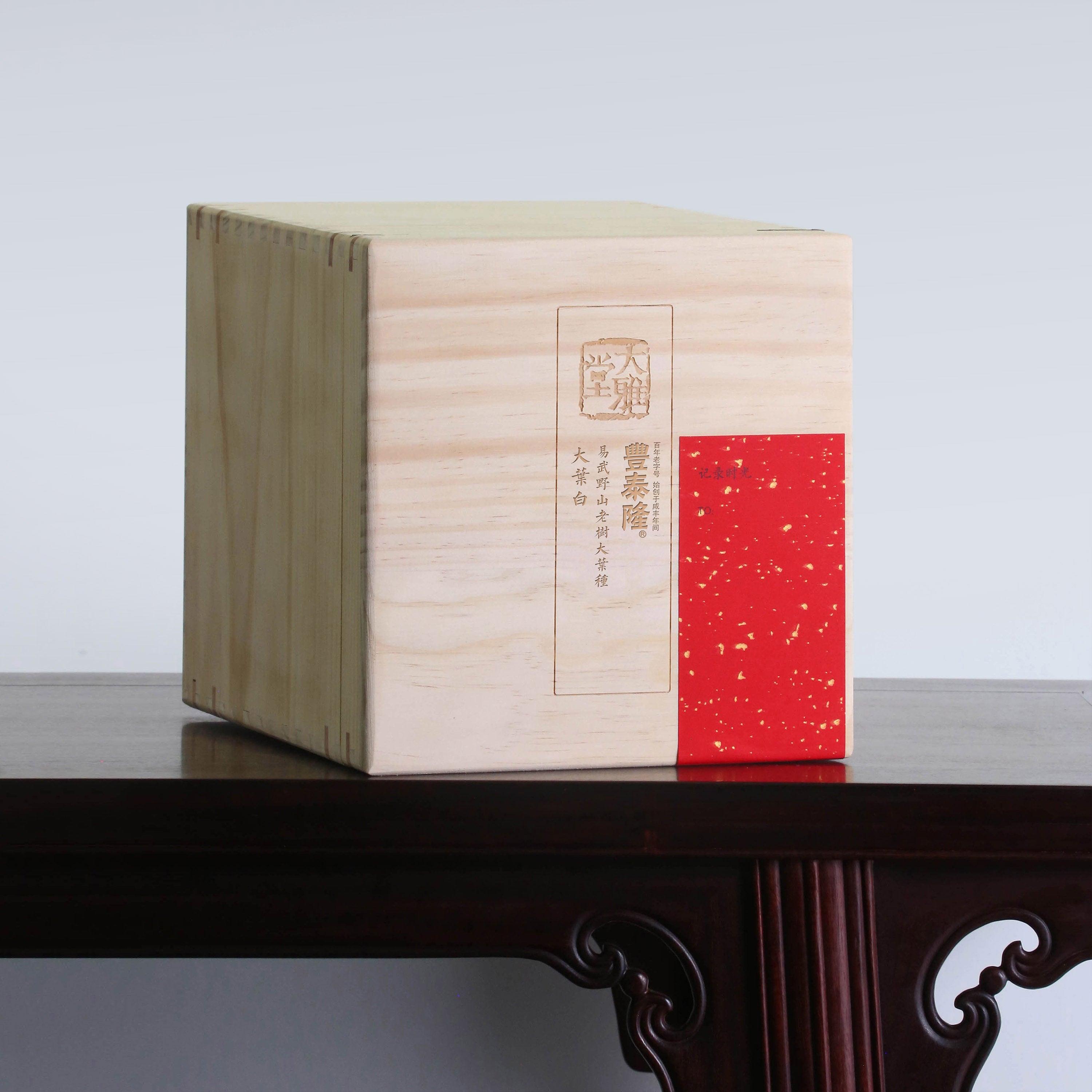

Wooden box packaging with a sealed bag inside.

Storage Guide for Yiwu Wild Mountain Old Tree Large Leaf White Tea

This white tea, made from wild, ancient tree, large-leaf variety, has a rich internal quality and potential for transformation. Storage requires a balance between "freshness preservation" and "slow transformation," with the following key points:

Core Storage Principles

Avoid light, high temperatures, and odors.

Temperature & humidity: Temperature 15-25℃ (avoid high temperatures that accelerate oxidation), relative humidity 50%-65%;

Light Protection & Ventilation: Keep away from direct sunlight (to prevent the decomposition of theaflavins and darkening of the tea liquor) and place in a well-ventilated area.

No odor interference: Do not store with items that have odors such as oil fumes, spices, or cosmetics, as the tea will absorb odors and destroy its original honey and aged aroma.

Container selection

Short-term storage (within 1 year): Use a purple clay pot or ceramic pot with air vents (choose a capacity matching the tea quantity to reduce residual air inside the pot). Seal the lid tightly immediately after taking tea, balancing freshness preservation and slight air permeability.

Long-term storage (over 1 year): Wrap the tea in an aluminum foil bag (vacuum-sealed to semi-vacuum with a small amount of air left) + a kraft paper box (wrapped in moisture-proof paper). Store in a cool, dry storage cabinet to prevent moisture while allowing slow transformation.

Taboo

Avoid store in the kitchen/bathroom: oil fumes, moisture, and odors will directly contaminate the tea leaves;

Avoid store on the balcony/windowsill: direct sunlight will cause the aroma to dissipate and the flavor to become bland;

Avoid frequent stirring: Frequent opening of the container will disrupt the temperature and humidity stability and accelerate the evaporation of flavor.

Post-Storage Transformation and inspection

Check the tea by opening the box or pot once every 2 months. Observe if there is mold or unusual odors — the tea should retain its natural honey fragrance and aged aroma when stored properly. With proper storage, the tea will gradually develop a richer woody fragrance and jujube aroma within 3-5 years, and the smoothness of the tea liquor will also improve.

Shelf life

The above storage method allows for long-term storage.