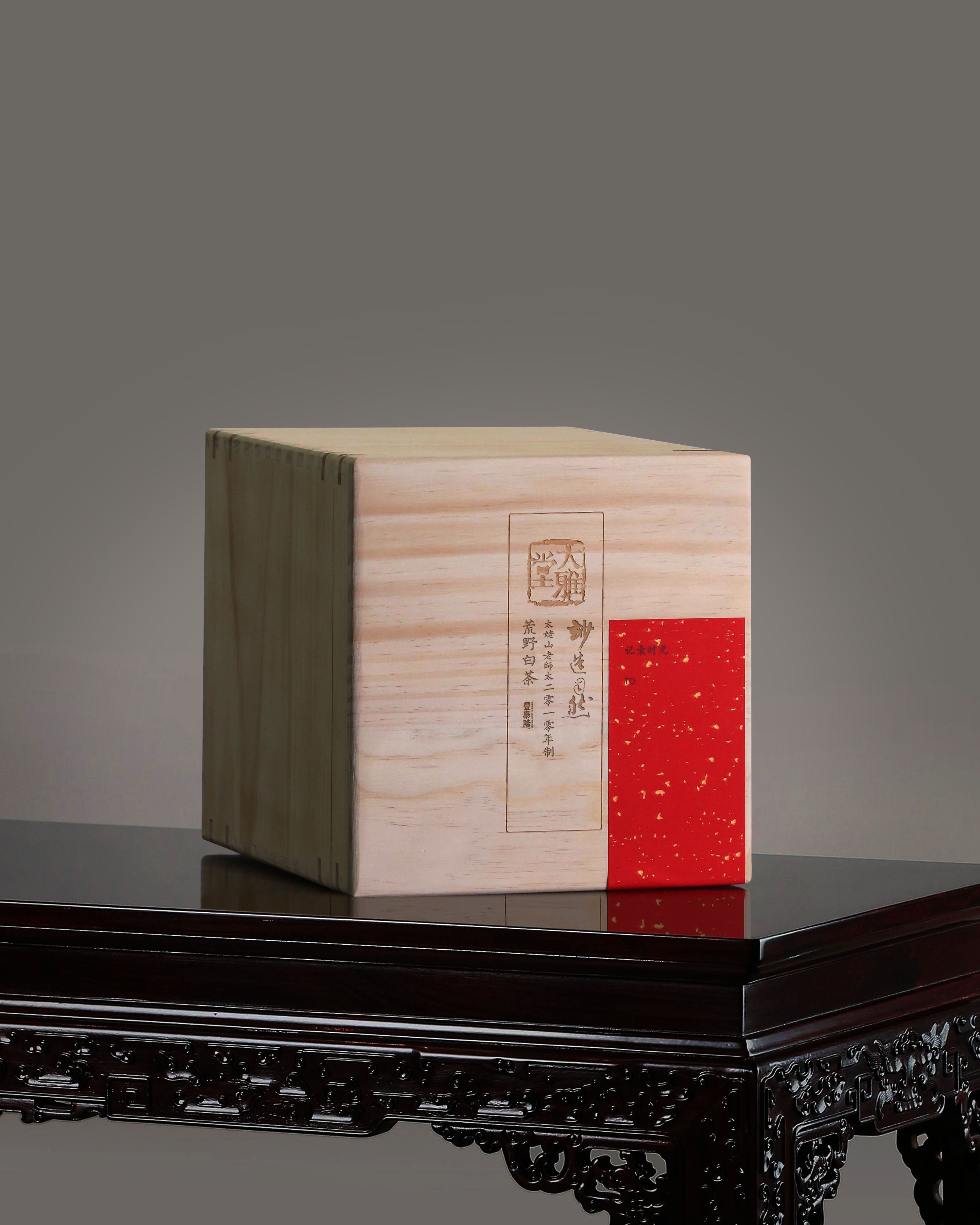

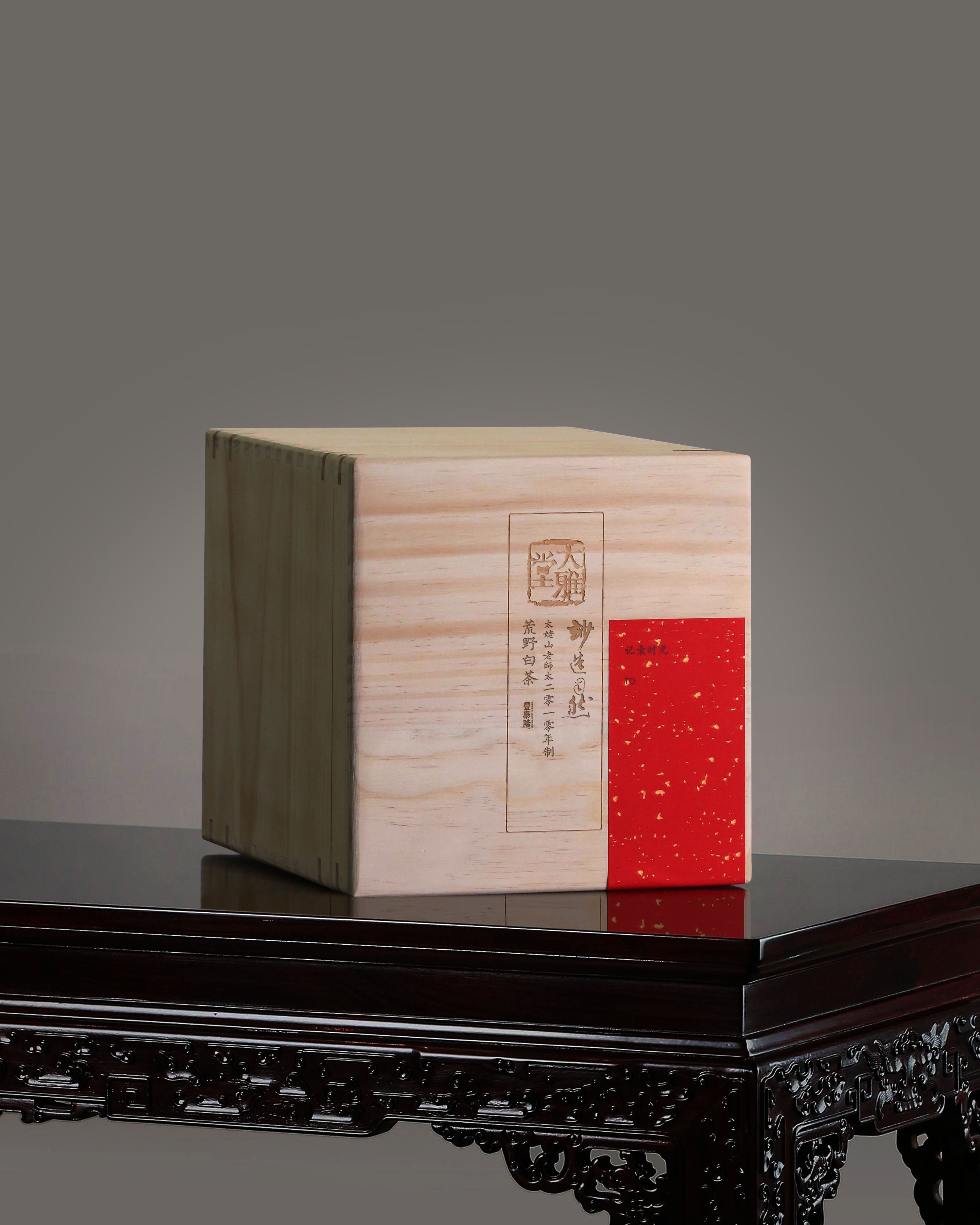

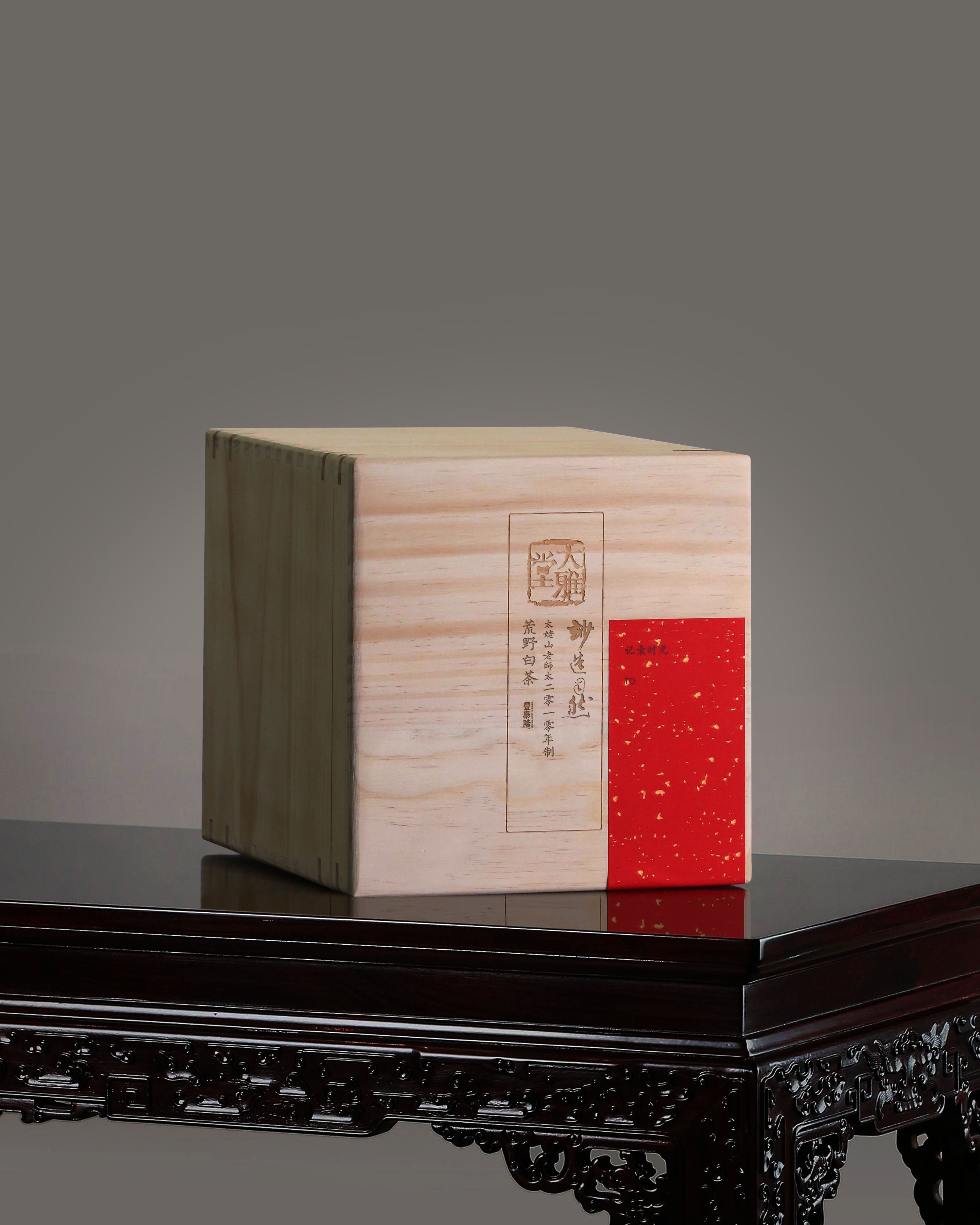

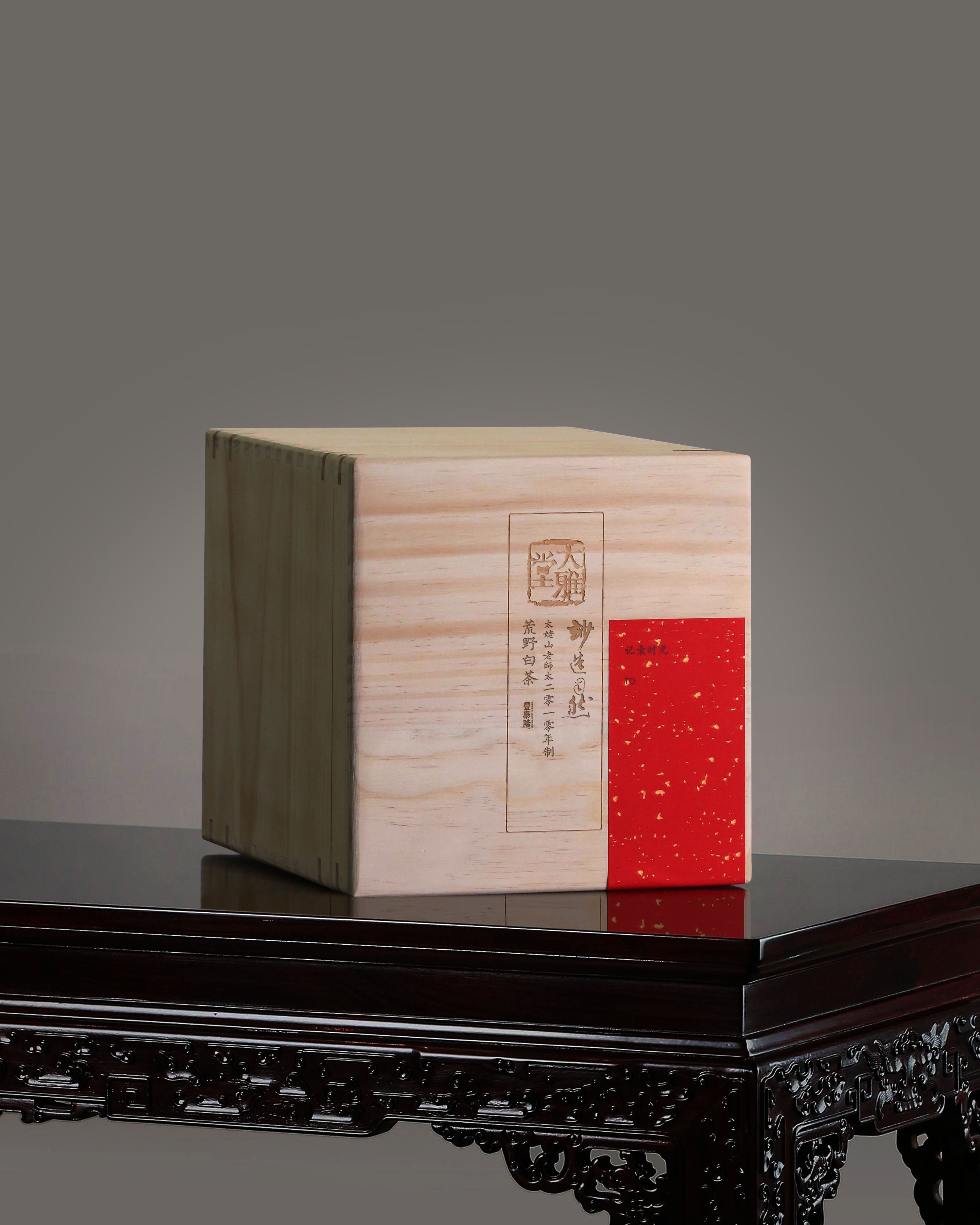

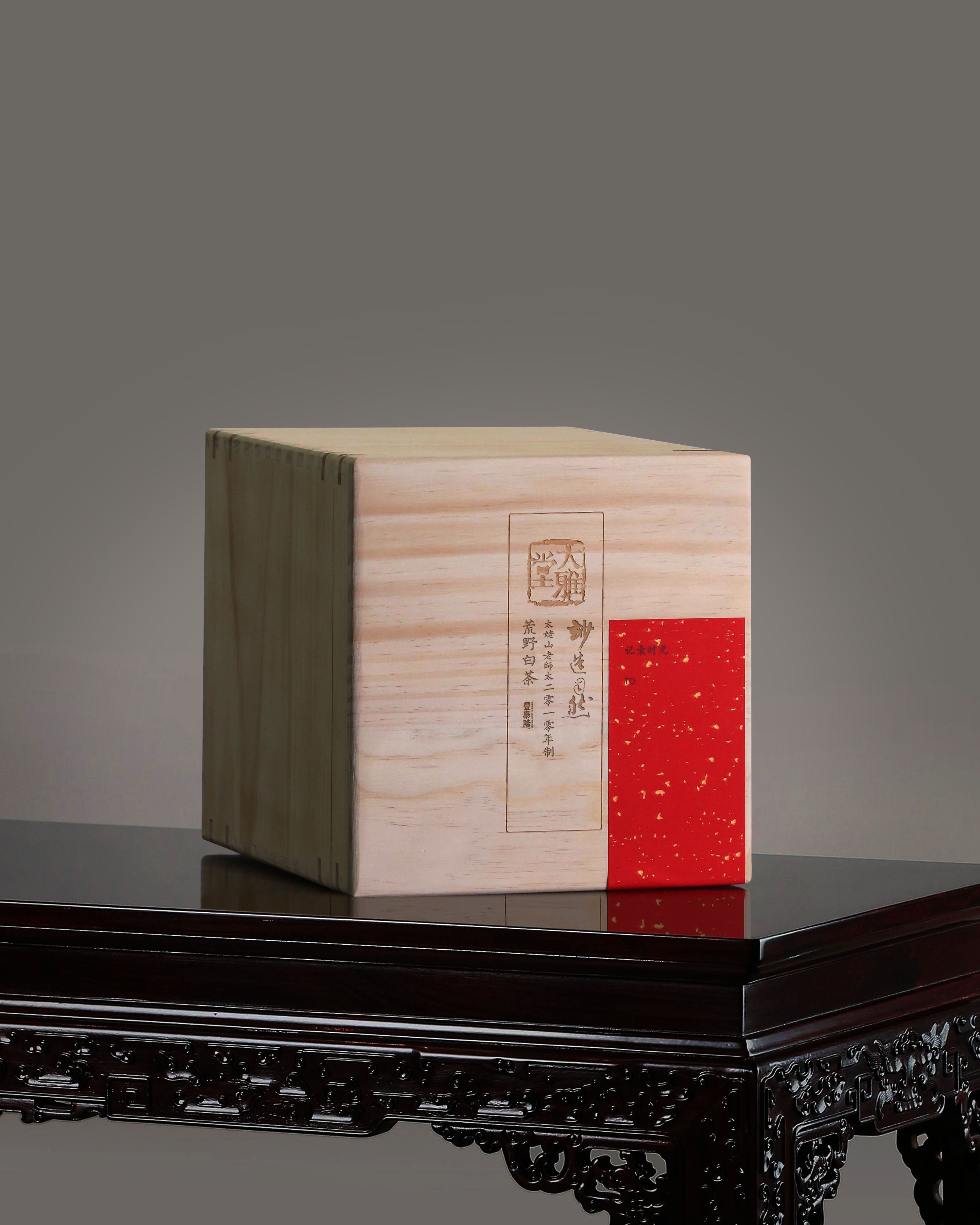

2010 Taimu Mountain Senior Buddhist Nun Craftmade Wild White Tea

2010 Taimu Mountain Senior Buddhist Nun Craftmade Wild White Tea

2010 Taimu Mountain Senior Buddhist Nun Craftmade Wild White Tea

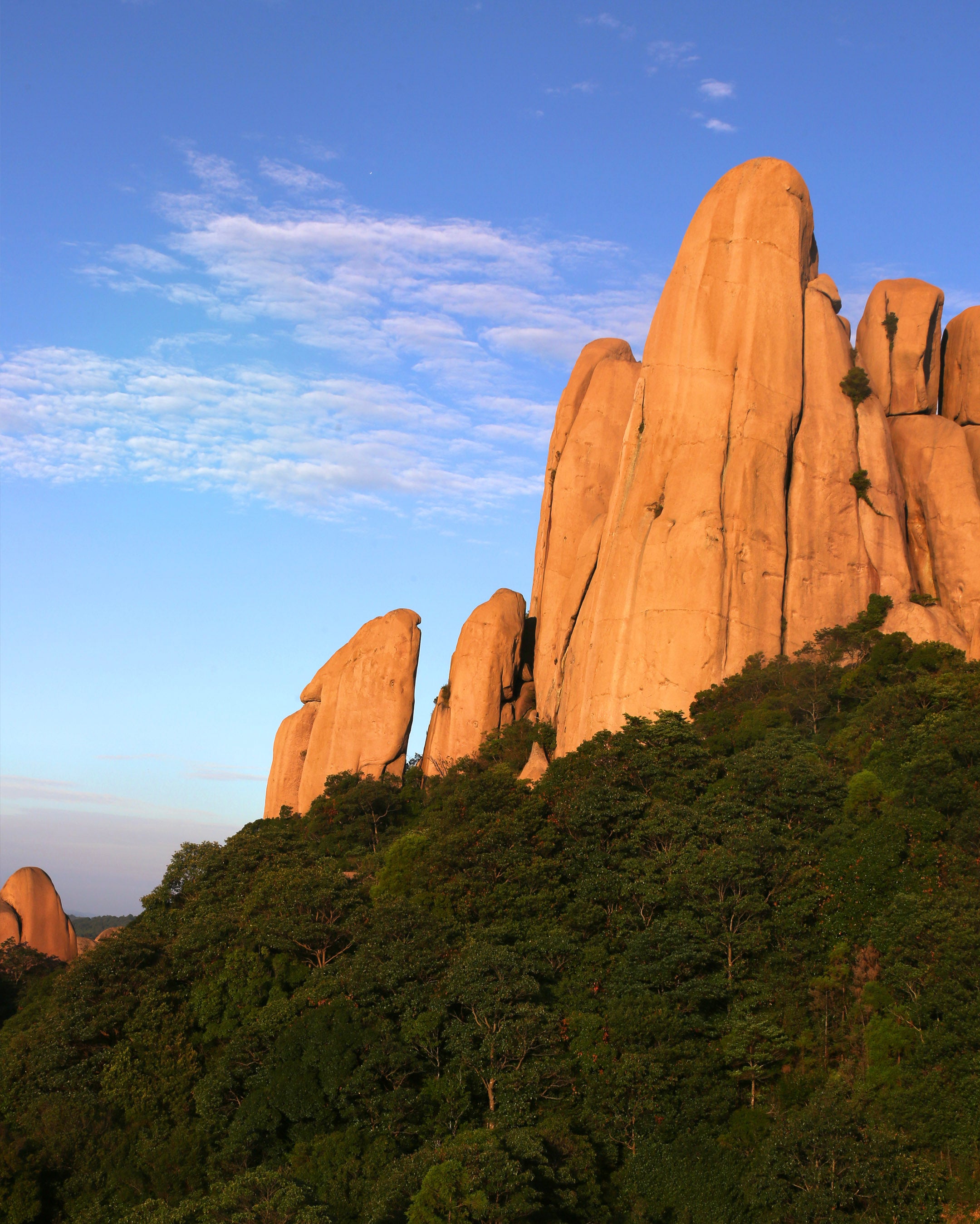

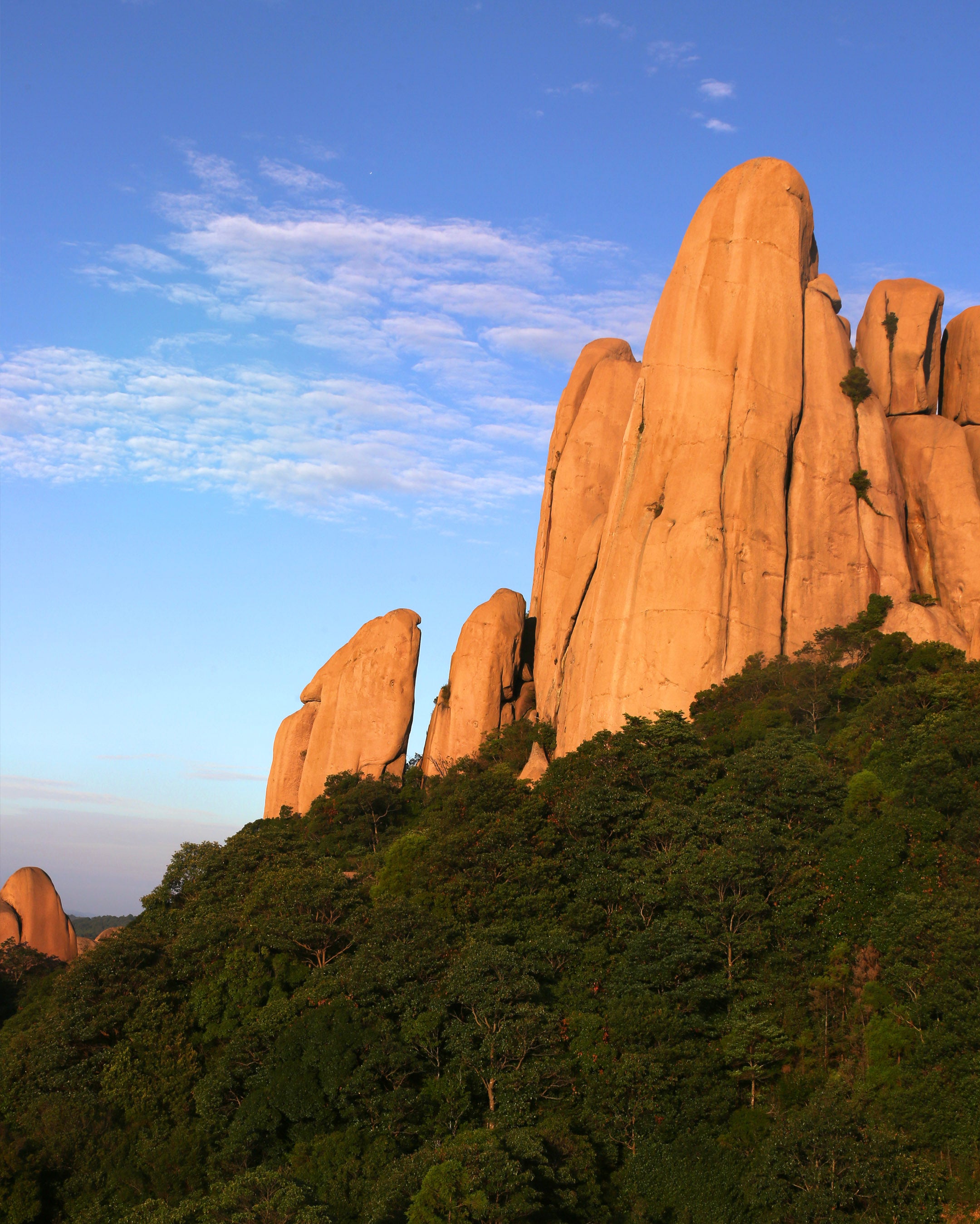

Three years later, in the bitter winter, I took my daughter to Mount Taimu again, hoping to spend the New Year with the Venerable Master in Bat Cave.

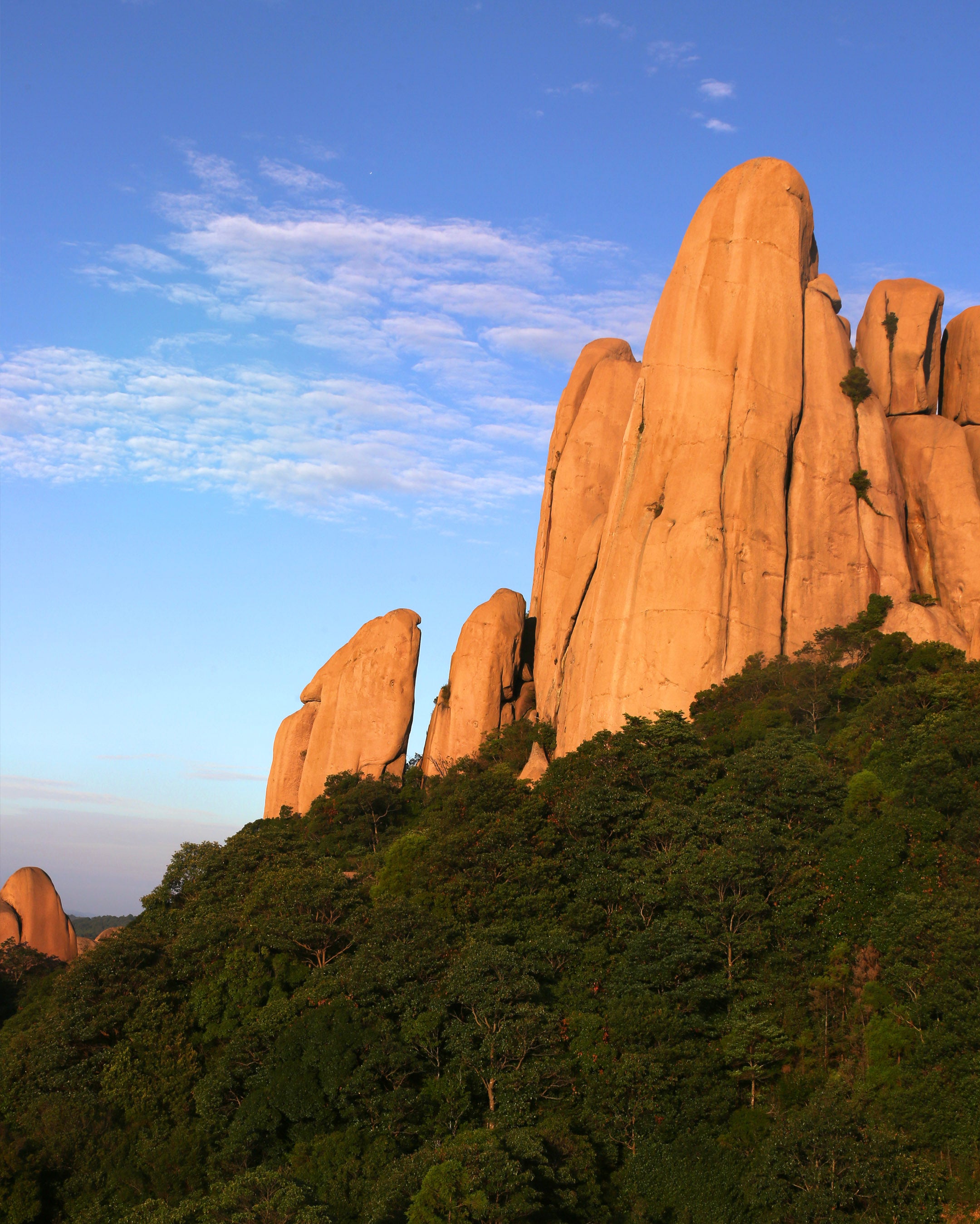

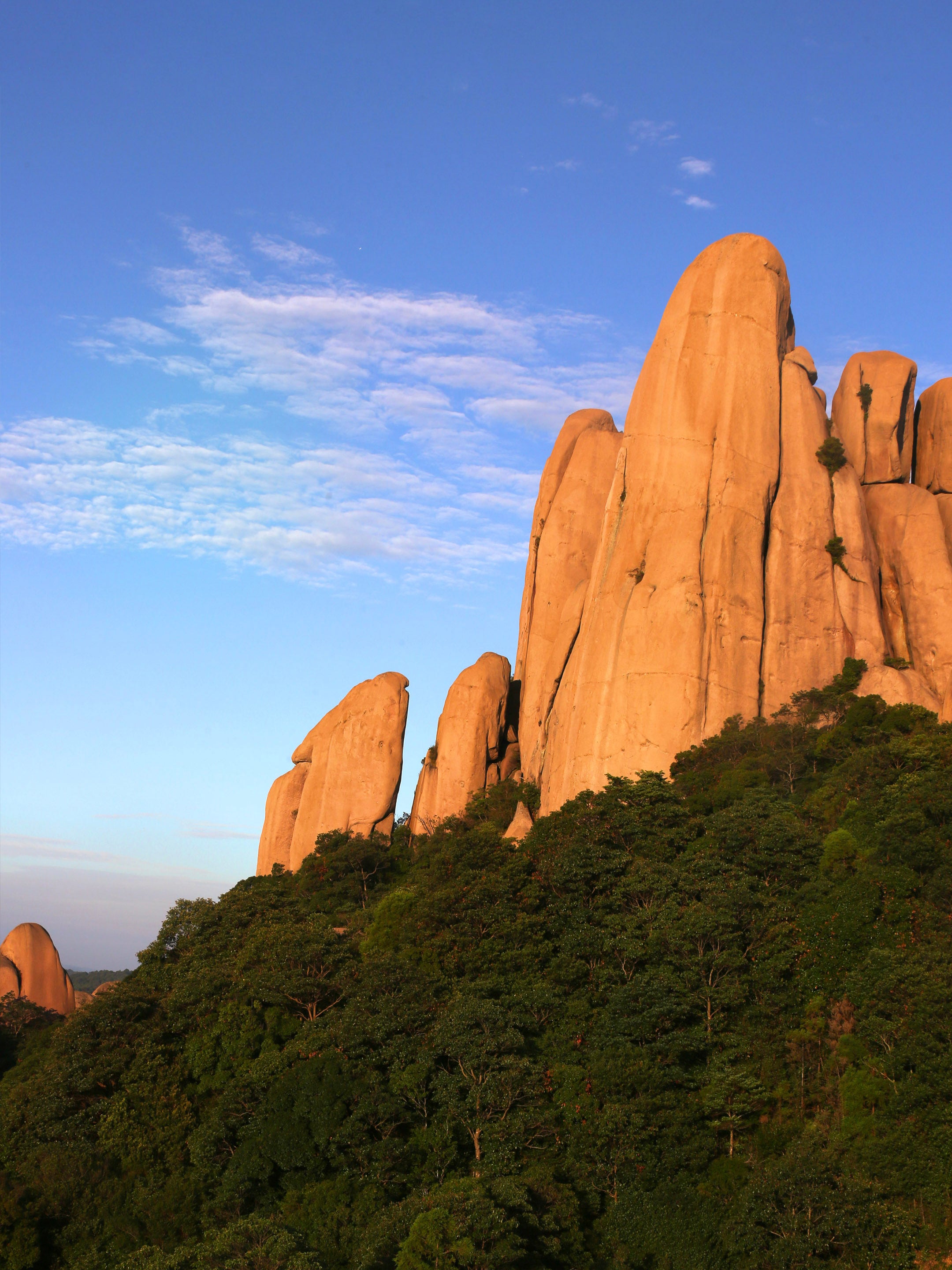

Stepping into Mount Taimu once more, the dusk hung heavy, the fairy-like mountain loomed in mist, and the red leaves in the mountains were still as gorgeous as ever.

Today is Lunar New Year's Eve. At 4:30 a.m.—a time when we are usually fast asleep—the Venerable Master and her disciples had already started their morning scripture chanting.

By 6 o'clock, the New Year's breakfast was ready. Before eating, they first offered offerings to the Buddha and all sentient beings. The Venerable Master and the newly arrived masters put on their solemn robes, rang the morning bell, and prayed for all living creatures.

The thick fog that had lingered for days unexpectedly lifted with the sound of the morning bell, and the sun rose on this New Year's day. The wild tea plantation burst with vitality under the sunlight.

A young monk told us that by the 16th day of the 8th lunar month this year, the Venerable Master would turn 93. Though she lived without an affluent material life, she was in exceptionally good health.

The Venerable Master said: "Making tea is a form of spiritual practice, and eating is also a form of spiritual practice."

Their daily life is disciplined and filled with a sense of ritual—perhaps they use these rituals to express gratitude and reverence. For us, rituals may feel restrictive, but for the Venerable Master, they have long become a natural habit.

The Venerable Master prepared a hearty New Year's meal for us, and thoughtfully let the child try "vegetarian fish" (a meat-free dish imitating fish). Before the meal, everyone joined their palms together and chanted: "We offer homage to the Buddha, to the Dharma, to the Sangha, to Amitabha Buddha, and to all sentient beings"—only then did they start eating with joy.

Bat Cave still adheres to the rule of not having dinner. It is said that this is to save food for all sentient beings and accumulate blessings for the next life. In every little detail, one can see the Venerable Master's piety towards all things. Wish everyone a happy New Year!

Seasons turn and suns rise and set over Mount Taimu. Indeed, making tea is a form of spiritual practice. For decades, she has been with white tea day and night—no one can say exactly how professional she is, yet no one dares to claim they understand white tea better than her.

Dewdrops glisten on the leaves of the wild tea plantation. Year after year, the Venerable Master always takes advantage of early spring to carefully make the first batch of fresh Silver Needle (a premium white tea), followed by Peony, and then Shoumei (another type of white tea).

At dawn, the Venerable Master does her morning scripture chanting. As the first ray of sunlight slants down on Mount Taimu, dewdrops moisten the earth, and white tea grows quietly;

At noon, the Venerable Master cleans the courtyard, while the white tea basks in the nurturing warmth of the sun;

As night falls, the Venerable Master practices in the Buddhist hall, and the white tea lies quiet and still in the night.

In this quiet Bat Cave Temple, as time flows by, the Venerable Master’s days pass quietly and without a trace—just like the dewdrops on tea leaves.

When I looked up again, Mount Taimu had already been shrouded in thick fog, cutting off the hustle and bustle of the world.

Standing beside the old temple, I watched that stretch of white tea bushes—still shrouded in ice and mist, exuding the essence of nature. The insect bites on the leaves were the marks left by the Venerable Master, who had been unwilling to harm the insects.

Fog lingered on the tea leaves all day long: it turned to water, dripped down, and condensed again—dripping and condensing repeatedly… The fog had been particularly thick these days. The door of Bat Cave Temple was half-open, and the Venerable Master no longer climbed the hills to check on the tea plantation.

She said she knew how to make white tea, as well as black tea and green tea, yet she sighed that she no longer had the strength to make tea this year. Even so, she still wished to make some green and black tea from Mount Taimu for us to taste.

A new young master at the temple said the Venerable Master was over ninety years old, and the temple would soon be taken over by the newly arrived senior master. A twinge of sorrow welled up in my heart—I feared that stretch of wild tea plantation and the vegetable plot might be left to waste away.

This farewell might be forever, making the time we spend together now all the more precious. Bat Cave, the Venerable Master, the tea plantation, this pure land—they will likely become warm yet out of reach memories in my heart forever. But the days and nights when the Venerable Master accompanied the white tea still flow clearly in my mind.

The senior Buddhist nun’s Wild Tea Garden

Celebrating the New Year in Bat Cave

Happy New Year🧨

The Turning of the Seasons

2010 Teacher's Tasting of Taihuang Wild White Tea

A tiny leaf beside the old temple on Mount Taimu

"Ice and mist" encapsulate the essence of the mountains and fields, and its natural flavor is left for others to describe.

Fifteen years have passed.

Long gone are the days of youthful naiveté.

It has developed a unique, mellow character that is characteristic of aged white tea.

Year : 2010

Grade : Top-grade Shoumei

Origin : Taimushan Nature Reserve

Varieties: Wild sexually propagated varieties: Fuding Da Bai Cha, Da Hao Cha, mixed with native ancient tea trees from Taimu Mountain.

Process: Traditional process of natural withering and gentle drying without frying or kneading.

I. Dried Tea

Predominantly dark brown and bronze in color, with intact buds and leaves, and a few scattered insect holes. When dry, it has a strong aroma of jujube and medicinal herbs, mixed with a warm, sweet scent from sun-drying, and no off-flavors.

Dry tea: predominantly dark brown and bronze in color, with intact buds and leaves.

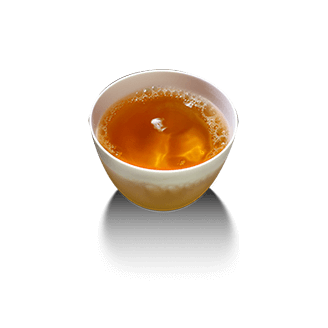

II. Tea Color <br />When brewed with boiling water, the tea is a clear, deep amber color, with fine hairs clinging to the cup wall; it is thick, smooth, and clear. When boiled, the tea color deepens, and the aroma of dates and herbs becomes stronger.

Tea color: A clear, deep amber color, with fine hairs clinging to the cup wall.

III. Aroma <br />Cover aroma: A blend of medicinal (mellow like licorice) and jujube aroma;

Aroma at the bottom of the cup: After cooling, it reveals a wild honey aroma and a warm, sun-dried feel;

Base notes: woody sweetness.

IV. Taste <br />It is smooth and mild on the palate, with a rich and sweet taste. After swallowing, it leaves a lingering sweet aftertaste and a warm feeling in the throat.

Tasting Summary: <br/>This is a gift from the terroir of Taimu Mountain and fifteen years of time. The insect-like holes reveal compassion, the aged aroma reveals character, and slow cooking brings out the gentleness of time and the true flavor of nature.

Changes in key indicators during the aging process of white tea

Appearance Indicators <br/>Dry Tea Color: New white tea is mostly green and white. As it ages, the color gradually deepens in 1-3 years, turns into a deep apricot yellow after 3 years, increases in brown after about 5 years, and is mainly brown after 7 years, mixed with white, yellow or red.

Tea Leaf Appearance: Fresh white tea leaves are relatively intact and unfurled, with vibrant stems and leaves. Aged white tea leaves become slightly wrinkled, and the stems appear drier, but still retain a certain degree of resilience. For compressed tea cakes, well-aged cakes are tightly pressed, but the leaves easily disperse when broken apart, without crumbling excessively. (Note that white tea cakes are generally made using a process from 2014 onwards; earlier white tea cakes were rare, and those older than this year are either newly pressed from old tea.)

Aroma Indicators <br/>New tea stage: Mainly characterized by downy aroma, light aroma, and floral aroma. For example, Baihao Yinzhen has a rich downy aroma, Bai Mudan has a light floral aroma, and Shoumei has a faint grassy and downy aroma.

1-3 years: The aroma gradually weakens, the floral fragrance begins to transform, a faint aged fragrance appears, and there may also be a slight fruity fragrance.

3-5 years: The aroma becomes more pronounced, and the floral fragrance further transforms into lotus and jujube fragrances. White Peony and Shoumei teas have a more prominent jujube fragrance at this stage.

5 years or more: The aroma of herbs and wood gradually appears and becomes rich, becoming the dominant aroma, while the aroma of aged wood and jujube still exists.

Soup color index

Around 1 year: The soup is light yellow, clear and bright, with a rather elegant color.

After about 3 years: the tea soup turns apricot yellow, slightly darker than when it was new tea, but still has a good brightness.

Around 7 years: The tea soup turns orange-yellow, the color deepens further, and the tea soup becomes more mellow and has a better texture.

10 years or more: The soup color is bright orange-red, as vivid as amber, and the color changes relatively steadily with the number of brews.

Flavor Indicators <br/>New Tea: Fresh and refreshing flavor with a clean grassy and downy aroma, and a quick but not long-lasting aftertaste.

1-3 years: The freshness decreases, the tea soup begins to become mellow, the flavor becomes richer, the aftertaste becomes stronger, and the nature of the tea changes from cool to warm.

3-5 years: The mellowness is further enhanced, the taste is smooth and sweet, the tea soup is smooth on the palate, the aftertaste is long-lasting, and the aged aroma gradually becomes more obvious.

5 years or more: The flavor is mellow and full-bodied, with a smooth texture. The aromas of herbs and dates are infused into the tea soup, with a long-lasting sweet aftertaste. The tea is mild and more resistant to brewing.

Leaf Infusion Indicators <br/>Color: Fresh tea leaves are predominantly green with a slight yellow tinge, appearing vibrant and glossy. As the leaves age, their color gradually changes to yellowish-green and then yellowish-brown. Aged white tea leaves (7 years or older) are mostly brown with a uniform color.

Texture: Fresh tea leaves are soft, elastic, and have good resilience. Aged tea leaves still retain a certain degree of softness and resilience, but compared to fresh tea, they will be slightly drier and harder, although they will not become brittle or mushy.

Each gram of tea carries a family's 174 years of day-and-night guardianship

Through six generations of tea masters' perseverance

Complex brewing

exacting attention to details

Only to help you taste the true flavor

of tea aroma

Let the essence accumulated over time unfold in boiling water.

2010 Wild White Tea Brewing

Tea Brewing Guide

Warming the teapot before stir-frying ( a key step for enhancing aroma):

Dry the tea maker, heat it over low heat for 30 seconds, add 5g of tea blocks, gently shake the pot by hand, and dry-fry for 1 minute (stop when you smell a slight charred aroma, do not burn it).

Brew tea with cold water:

Add 400ml of cold water, bring to a boil over high heat, then reduce to low heat and simmer for 2 minutes, keeping the water at the "crab eye" stage (small bubbles) for 2 minutes. Turn off the heat and let it sit for 5 minutes.

The tea soup is a deep amber color, thick and creamy, with a blend of medicinal and subtle roasted aromas, making it perfect for warming up in autumn and winter.

Tips for continuing to cook:

The second boil involves adding warm water and boiling for 1 minute after it boils to avoid over-extraction, which would result in a diluted product.

If the tea leaves are not fully unfurled after brewing, they can be removed and gently broken apart by hand before being brewed again.

Soaking before boiling

The first three infusions (using a gaiwan/ Yixing teapot) are to awaken the aroma of the tea.

First infusion: Pour boiling water at 100℃ around the wall, steep for 8 seconds, the soup will be light amber in color and have an initial sweetness;

2nd-3rd infusion: Extend to 10 seconds, the color of the soup deepens, the aroma of aged wine and herbs gradually emerges, and the taste becomes mellow.

Transfer the tea leaves to the brewing vessel (to release the aftertaste, and brew again 3 times).

Preparation before cooking:

After steeping the tea leaves three times, put them directly into the tea maker and add 300ml of cold/warm water (cold water will bring out more flavor, while hot water will save time).

If the tea leaves are broken, a tea strainer can be used to wrap them to prevent the tea soup from becoming cloudy.

Firepower control:

First step: After bringing to a boil over high heat , immediately reduce to low heat and simmer for 1-2 minutes. Turn off the heat and let it sit for 3 minutes (the soup will be red and thick, and the texture will be like rice water).

Second boil: Add 200ml of warm water, bring to a boil over high heat, then simmer over low heat for 1 minute and let it steep for 2 minutes (the flavor will still be sweet and mellow, and the aroma will last a long time).

Third step: Add a small amount of hot water, bring to a boil, then turn off the heat and let it steep for 5 minutes (the aftertaste is sweet and refreshing, and it can be used as a "tea to quench thirst").

Tips for drinking

It is recommended to drink the brewed tea after it has cooled slightly (60-70℃) to experience the "gelatinous texture and smoothness in the mouth" and the "sweet aftertaste in the throat".

When brewing tea, uncover the teapot lid by 1/3 to avoid "over-simmering" and producing a cooked taste.

water quality

Choose qualified purified water; do not use alkaline mineral water .

(The water quality of commercially available mineral water varies depending on the water source and the brand. So-called "high-quality mineral water" may cause loss of functional components and inhibition of aroma in tea.)

Part 1: The Effects of Alkaline Water on Tea

1. Effects on the color of tea liquor

green tea:

Under alkaline conditions, chlorophyll is easily destroyed (chlorophyll stability decreases at pH > 8.0) , causing the tea liquor color to easily change from bright green to yellow or dark yellow, resulting in turbidity , especially noticeable when brewed at high temperatures. Flavonoids (such as catechins) in green tea are easily oxidized in an alkaline environment, exacerbating the darkening of the tea liquor color.

black tea:

Theaflavins (bright orange-yellow) are easily oxidized to thearubigins (dark red) under alkaline conditions, and further generate dark brown, causing the soup color to change from bright red to dark and lose its transparency .

Other types of tea:

The color of oolong tea, white tea, and yellow tea may be darker due to alkaline water. The color of black tea (such as ripe Pu-erh) will become more turbid, and the color stability of aged aroma substances will also be affected .

2. Impact on taste and texture

Analysis reveals differences:

Tea polyphenols and caffeine: lead to insufficient concentration and bland taste . An alkaline environment inhibits the dissolution of tea polyphenols (bitter substances) and caffeine, reducing the bitterness of the tea soup.

Amino acids and sugars: Disruption of amino acid structure reduces the freshness and crispness.

Mineral influence: Alkaline hard water (containing more calcium and magnesium ions) combines with tea polyphenols to form insoluble precipitates (such as "cloudiness after cooling"), resulting in cloudy tea soup and a rough taste .

Balance of taste: It significantly affects the "richness" of tea soup for teas that rely on polyphenols to support their taste (such as raw Pu-erh tea and high-roasted rock tea), with no noticeable aftertaste and an overall taste that is bland and coarse .

3. Effects on aroma

Volatile aromatic substances: An alkaline environment may accelerate the degradation or transformation of aromatic substances (such as aldehydes and alcohols), resulting in a single aroma profile, especially in light-aroma teas (such as jasmine tea and Anji white tea), where the floral fragrance dissipates easily and may even develop a "mushy" taste.

Aged aroma and woody aroma: For fermented teas such as black tea and aged Pu'er, alkaline water may slightly highlight the aged aroma (pH>8.0) and suppress the fruity or honey aroma.

Second: The adaptability of different types of tea to water quality

1. The interaction between the physicochemical properties of water and tea components

-

Hard water (>120 mg/L CaCO₃) : Calcium ions combine with tea polyphenols to form precipitates, reducing the astringency of tea soup (EGCG binding rate can reach 23%), but losing antioxidant activity (Food Chemistry, 2018); Magnesium ions promote caffeine dissolution, and every 1 mg/L increase in magnesium can increase the caffeine concentration by 0.8% (Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2020).

-

Soft water (<60 mg/L CaCO₃) : Theaflavin dissolution rate increased by 12%, and the brightness of the tea soup increased (L* value increased by 3.2), but the amino acid extraction efficiency decreased (Food Research International, 2019).

2. Supported by scientific experimental data

-

Longjing green tea brewing experiment (TDS = 50 vs 300mg/L) : The amino acid content of the tea soup in the soft water group (1.2mg/mL) was significantly higher than that in the hard water group (0.8mg/mL), but the caffeine content was 18% lower (China Tea Processing, 2021); Sensory evaluation showed that the freshness score of the soft water group was 1.7 points higher (out of 9), while the body of the hard water group was 0.9 points higher.

-

Research on water quality suitability for Wuyi rock tea : Water containing trace amounts of sulfate (20-50 mg/L) can increase the dissolution of cinnamaldehyde, a characteristic aroma compound of cinnamon, by 24% (GC-MS detection), and significantly enhance the rocky aroma (Tea Science, 2020).

3. Water quality selection recommendations (based on tea)

|

Tea |

Ideal TDS |

Recommended pH |

Key ion requirements |

|

FTL Green Tea |

30-80mg/L |

6.8 |

Ca²⁺<15mg/L, Mg²⁺<5mg/L |

|

FTL Oolong Tea |

80-150mg/L |

7 |

HCO₃⁻ 40-60mg/L |

|

FTL Black Tea |

100-200mg/L |

6.8 |

K⁺ 2-5mg/L, SiO₂ 10-15mg/L |

|

FTL Pu-erh Tea |

50-120mg/L |

6.8 |

Fe³⁺ < 0.1 mg/L |

4. Examples of the impact of special water quality

London tap water (high hardness) : When brewing black tea, the formation of oxalool-calcium complexes leads to "cold turbidity" appearing 30 minutes earlier, with the turbidity (NTU) of the tea reaching 12.5, which is significantly higher than that of the soft water group (NTU = 4.3) (Food Hydrocolloids, 2019).

Kagoshima hot spring water (containing sulfur) : Sulfides react with theaflavins to form methyl flavonoids, which reduces the umami intensity of sencha by 37% (*Journal of the Japanese Institute of Food Science and Technology, 2022).

The quality of water from a particular source can enhance the color, aroma, and flavor of local tea, but using local water requires systematic professional knowledge and is very costly. For non-professionals, mastering the basic principles of "soft and clean water + temperature control" is far more practical than pursuing famous springs from their place of origin.

The precise matching of water and tea is essentially a dialogue of geographical genes, which needs to be built on a multidisciplinary system of geology, food chemistry, heat transfer and other disciplines, and cannot be covered in just a few lines of web pages.

The UK-based AquaSim laboratory has simulated 12 core indicators of Tiger Spring water. However, it lacks the original spring's microbial community (such as Nocardia tea-loving bacteria), resulting in a 27% difference in post-fermentation flavor. In addition, the operation is complex: it requires mastering the "listening to the spring while boiling water" method (stopping the fire immediately when the water first boils), and a temperature error of more than 3°C will disrupt the flavor balance.

The charm of tea ceremony lies in appreciating what suits one's taste.

A pot of purified water is enough.

Don't be trapped by the mystique of water quality.

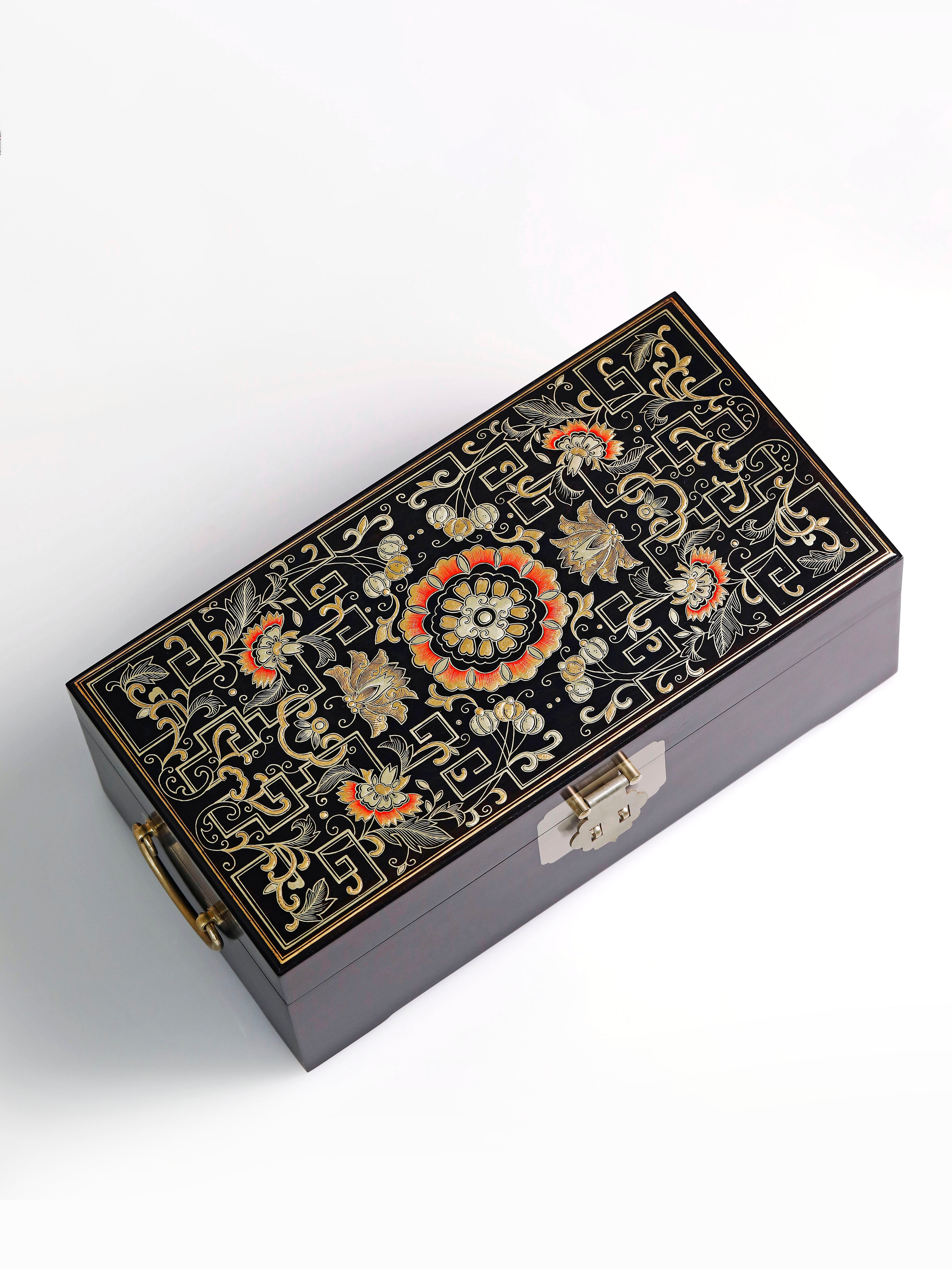

Wooden box packaging with a sealed bag inside.

The charm of tea ceremony lies

in what suits you as precious

A pot of pure water is enough

Don't be trapped by water quality metaphysics

White tea is cold in nature, and its cooling effect increases with age. It can be used as medicine after three years and become a treasure after seven years of storage.

White tea storage

White tea storage

Avoid light, high temperatures, and odors.

Temperature & humidity: 15-25℃, 50%-65% (to prevent mold and loss of fragrance);

Light Protection & Ventilation: Keep away from direct sunlight (to prevent the decomposition of theaflavins and darkening of the tea liquor) and place in a well-ventilated area.

No odor interference: Keep away from sources of odor such as cooking fumes and spices.

Container selection

Short-term (within 1 year): Purple clay/ceramic jar with ventilation holes (for preservation);

Long-term (over 1 year): Aluminum foil bag (semi-vacuum) + moisture-proof cardboard box (aids conversion).

Taboo

Avoid Storing In: kitchen, bathroom, balcony, or refrigerator.

Minimize container movement. Check every 1–2 months: the tea should remain loose, free of mold, and odorless.

Shoumei/Gongmei: Store per long-term standards — they easily develop jujube aroma with aging.

Peony/Silver Needle: Short-term storage can use a purple clay jar; long-term storage requires moisture protection.

Shelf life

The above storage method allows for long-term storage.